On Greg Tate and the Critic's Role In Community

A year after his unexpected passing, the writer/curator/musician/musicker casts an undeniable influence on how to balance critical and creative work. Plus: some great Tate links.

For me, 2022 has been a year marked by death and illness, grief and sorrow, and it was the critic Greg Tate’s transition from this world a year ago, which set the stage for many of the events that followed. My own “formal beginning of the long bereavement.”

Tate’s abrupt passing prompted a lot of familiar factual gasps — “so young” (aged 64), “so unexpectedly” (cardiac arrest), “with so much life left in him” (Greg’s last year saw him busier than ever, appearing in numerous documentaries, curating a museum show, constantly playing out with his “jazz-rock” band Burnt Sugar). It also triggered a stream of ruminations about a person whose work and presence proposed a larger-than-life understanding of Black culture’s beauty, fluidity and influence. The contemporary commentariat laments a modern world which lacks cultural critics who also qualify as popular public intellectuals. Well, Tate covered these roles with aplomb, was good at it, and seemed to enjoy it. *Maybe* he wasn’t considered for the part because he was Black, or that his knowledge reflected a world which media institutions are willfully blind to... Whatever it was, many writers and artists of my generation spent their adult lives learning by Tate’s example, some by attempting to imitate the dexterity of his prose, or mimic the wisdom that hypertextually strung his pearls together; some simply by pursuing every opportunity to engage his mind wherever it popped up, following the leads rather than aping the style. That this mighty Greg Tate very suddenly no longer walked the earth, was a stark reminder of mortality’s unfairness and totality.

But that wasn’t all - at least not for me. There was something else Tate did that spoke to a new kind of imagineering of how a person’s creative and critical and community lives combined and intertwined, how what are oft-considered to be splintered roles might create a unified being. The Walk and the Talk. Where I considered Tate a paradigm-shifting model of what a critic could be was less about his individual projects or streams of thought — though his brilliance always has me reaching for a pencil and notebook — than in how his prodigious expressions stitched together who he was, what he made, and what it was all for, into a remarkably holistic worldview. The rigid doctrine J-schools impart and MSMs safeguards is that a critic works best when they act less as a member of the community, and more as an impartial observer, abstaining from personal biases. Whereas Tate brought his community-schooled partiality to pretty much everything he did. A multi-generational perspective informed all the work. His point of view never seemed to aspire to projecting omniscience; it was deeply informed, personal and lived-in, not flat or theoretically cumbersome. And yet his theory game was also hella-tight, but rather than conceptual or academic in its delivery, it was applicable, colloquial, Black ontological from experience not from study. Fun even. To make a difficult point, he’d maybe tell a story about his best friend — but when that friend is Arthur Jafa, a pastiche of jokey anecdotes, “secret” (to some) communal histories, post-structural postulation, and the potential creative way forward, easily slid into plain-speaking slanguage that provided an empirical blow against the empire. With Tate, the personal was the philosophical was the philanthropic was the fire.

I’ve discussed Tate’s work in both of the university writing classes I’ve taught, and while the prose was always the clear lede, it was his evocation of self in-the-world — for many pre-personal-essay years, considered a hallmark of mediocre critical writing — that I’d point out. And continue to soak in. Because the way Tate invoked that collective knowledge to help manifest a personal critical POV was not an ego trip, or at least not primarily one. It was a celebration of people, some famous, most not, many of who he knew. His communal eye (and I) is everywhere you read: exuding cutting-edge Blackness while fluent in the white mainstream culture he also grew up on, which continued to peak his interest, and whose codes he could expertly cite, skewer and flip. (“Bowie was so avant-garde he tipped over into the Avant-'Groid,” goes one of the many great lines in a 2016 eulogy for Ziggy Starman.)

Tate’s humanism was not simply observational, it was participatory. His co-founding of the Black Rock Coalition, a community organization that tried to cut through the racism of New York’s ‘80s punk rock scene, was a way to organize the musicians and musickers, and help lift their art together. Which is exactly what happened when Living Colour, a BRC cornerstone, broke-through, and was opening for the Rolling Stones in stadiums just a couple of years after playing CBGBs. Burnt Sugar, the electric jazz-rock-polyglot group he founded in the late-‘90s after studying the conduction method of big-band improvisation with Butch Morris, was a community in its own right. Burnt Sugar featured a regularly rotating cast of incredible players (some famed, some about to be, some quietly heroic), performing a constantly evolving repertory which reflected the diverse interests of its leader and members, often for free, taking advantage of the city’s arts institutional largess and Tate’s long-standing connection to them, presenting the music back to the people who inspired it. (And, in fact, Burnt Sugar continues, even as Tate is gone.) The principles weren’t just part and parcel, they were out in front.

Tate and I talked about this methodology on a few occasions over the course of the far-flung contexts of our acquaintance. The first meeting involved him actually complimenting me on my “music curation” for Black President: The Art and Legacy of Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, the great 2003 group exhibit at the New Museum which was put together by my friend Trevor Schoonmaker. The “work” was nothing more than a long mixtape, but the fact that one of my writing heroes offered a handshake to this Russian immigrant kid for his attempt to musically contextualize the influence of an African music legend, forever stuck with me. He reached out when he did not have to. So I reached out whenever I worked on something that might interest him, and had a budget — only to find out that a budget was not always foremost on his mind, a lesson it took me too long to understand.

Yet in saying “no” far more often than he said yes, Tate never dismissed me. It bummed me out deeply that he chose not to contribute to the 2013 daily newspaper about New York music I helped publish under the auspices of the Red Bull Music Academy — cheeky jokes about the hyper-caffeinated drink and “content advertising” were indeed cited in his reluctance, but a few years later he did do a piece for RBMA, which I took to mean that the quality of the work trumped the toxicity of brand-affiliation. In 2014, I started making stuff for AFROPUNK, a festival organization that on the one hand continued BRC’s mission of community Black rock and punk, and on the other, attempted to fold together revolutionary social potentialities with culture-capitalist aspirations. And though leery, Tate moderated a roundtable of a couple AFROPUNK-related events I produced at MoogFest that year, including a talk with Saul Williams and the artists Sanford Biggers and Marcia Jones called “The Nature of Creativity,” that mirrored some of his best writing, a spitting-and-cutting session that was also informative of Black creative perspectives. At AFROPUNK, I had a couple of opportunities to edit Greg — one was a piece I suggested (an obituary of the mighty jazz pianist Geri Allen, whom Greg went to school with at Howard), the other he wanted to do (a review of BlackKklansman). Otherwise, not wanting to deal with the company’s then-principals, he would holler at me to get him and his daughter passes to the Brooklyn festival, which I happily obliged. By the last year I worked there, the last pre-pandemic year, I even annoyed the bookers enough that Burnt Sugar got to play.

It all felt of-a-piece, that being a genius cultural critic was, in Tate’s case, *nothing more* than virtuoso representation of a community — of the brilliance of Blackness primarily, but also of a world where that brilliance informed a possibility unimaginable under white supremacist patriarchy, or without the public gifts that Blackness offers. As I’ve heard Jafa say, at times in Tate’s presence (and I am slightly paraphrasing here), “My work is, first and foremost, for Black people — but it’s not *not* for other folks as well.” Shortly before Tate passed on, he and I exchanged notes about him possibly being on Dada Strain Radio to discuss this community representation — and to talk about the meanings behind rhythm and improvisation, things I learned in large part from reading and following his work my whole life. Greg was non-committal in a way I’d grown used to him being, wanting to hear more. I mentioned that one of the people I’d already scheduled time with was Thulani Davis, the legendary critic/writer/editor/screen-writer/librettist who was also a bit of a mentor to him, having first met young Tate as a high-school student in Washington D.C., and then recommended his hiring at the Village Voice in the early ‘80s. I never heard back.

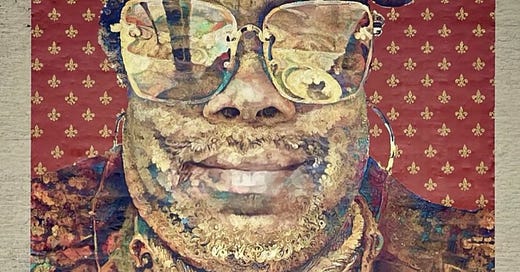

But I still see Greg Tate regularly. In June, a mural portrait of him was installed about a block away from where I often go to write, and his oversized grin, presented with colorful magnificence, greets me as I get out of the subway. Created by Dr. Nettrice Gaskins and installed by the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts just around the corner, it hangs at a major intersection in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, a neighborhood I’ve known most of my life as Black bohemia’s Brooklyn epicenter. The gentrification has hit these parts as hard as anywhere else in the rapidly changing borough. Still, there newly hangs Greg Tate, an embodiment of community knowledge, past and future, inferring connections between them all, his work and memory a forever-blessing, and a guide.

ADDITIONAL GREG TATE RESOURCES:

Michael Gonzalez is a writer dear to me, who was very close to Greg Tate for over 30 years. His memories of Greg Tate, “Afrodisiac: A Textual Meditation on Greg Tate” for LitHub, is a wonderful read.

The last few years of his life, some of my favorite Greg Tate came not via writing but in lectures. Most often when tag-teaming with one of his best friends, the film-maker Arthur Jafa, in conversations that were some of the most inspiring “performances” I’ve ever seen. These intellectual improvisations weren’t performative per se, but worthy of audiences, not only imparting incredible knowledge but showing the men’s shared love and respect for each other, like two soloists. (My first experience of it was in 2017, listening to them deconstruct Jafa’s then-new film “Love Is the Message, The Message is Death” for nearly 3hrs.) Many of these talks were taped by the institutions that hosted them, and are on YouTube — and I can not recommend them all enough. Here’s one from 2017, after another screening of “Love Is the Message…” at Duke University, moderated by the great Mark Anthony Neal.

It’s impossible to spotlight just a couple of Greg Tate reads, cause there were so many different kinds. Many of the best are collected on his two landmark collections of criticism, 1992’s Flyboy In the Buttermilk and 2016’s Flyboy 2: The Greg Tate Reader, both of which are widely available and must-owns. But should you want to dip your toe before you dive in, somebody put together a site called Greg Tate Was Loved, which archives a lot of his great works, both in the collections, and those not included.