Signs of the 2020 Times

The documentary and art values of Fred Tomaselli's front-page collages, and Dezron Douglas & Brandee Younger's pandemic livestreams

As New York limps into Lockdown#2, memories and phantom pangs of a springtime in quarantine have already begun surfacing in dreams, as references and phrases, excavated from their subconscious burial grounds to become part of a more permanent record. Remembering those first moments of deep insecurity isn’t simply a reference of the dread — cold March weather, confusion and frustration, the constant ambulance sirens and silent stats constantly rising. They’re also reminders of possibility that once seemed on offer by the shifting, slowed-down axis. Especially creative endeavors, which people said they’d previously put off for lack of time or concentration or newsfeed chaos, and would now turn to as productive relief. That’s not how it turned out for most of us — most, but not all. And now, just as we seem to be accelerating once more, we’re experiencing the first trickle of measured responses (as opposed to a fired-off riposte) to that initial world in slow-motion free-fall, which feels like both balm and another type of provocation.

For example, I fully remember the warmth of my couch when Dezron Douglas (bass) and Brandee Younger (harp) started their livestream duets series on a mid-March Friday (I wanna say the 20th). There was beautiful late morning (11a) light shining through their window and mine. They checked in to see if those of us tuned in on Facebook could hear them. We could, though the initial mic placement required some tweaking.

I’ve no memory of what pieces were played that day, but instantly the tone of the proceedings - the sound of the instruments, the musical selections, the pair’s presence with each other, and towards the audience — felt the best version of natural and medicinal. They didn’t attempt to be distracting or therapeutic in grandiose Wellness fashion — just friends finding a way to pass the time with each other and with us, while using the tools available to try make sense of whatever the fuck was going. (Often learning about the tools and circumstances in real time, just as we were. Leaving no irony that I would listen to them instead of tuning into the incompetent NYC mayor, who answered question on public radio at exactly the same time each week. )

Sometimes their version of comfort meant playing Stevie Wonder or Alice Coltrane, or a blues or a pop song; but at other times it meant discussing Dezron’s love of coffee, or the toilet paper crisis, which became a running joke that one sensed Brandee first tired of, but then began incorporating into the schtick and ended up writing a piece about. Theirs was a spectrum of feeling conveyed through music, with bashes of stand-up routine at a time when the whole idea of “routines” was disappeared. It effortlessly mutated into what those “artists” with big quarantine to-do projects all had in mind; except most of them/us lacked the capacity to pull it off, or didn’t consider that the trick is simply staying steady, adapting what you’re already doing, then focusing it on the circumstances at-hand.

By the time of June’s #BLM protests, when George Floyd death followed Breonna Taylor’s, and the video of Ahmaud Arbery’s, the sadness and anger of the Black community and all who stand with it, had already been an organic aspect of Brandee and Dezron’s performances. Being students of the jazz tradition, the history of Blackness in America resonated through their music every time they lifted their instruments — its oppression, its vitality, its strength in the face of subjugation both physically brutally and institutionally insidious. Yet the nature and tone of those Friday morning sessions changed accordingly, foregrounding communal pain and elegy, but also a streak of defiance with an air of joy, an essential ingredient to understanding what was happening.

Thankfully, they recorded it all, and are releasing some of its best parts (banter included - and toilet paper song included) on an album called Force Majeure (International Anthem). It’s named after a provision in most live performance contracts, which relieves both parties from meeting their obligations when certain circumstances beyond their control make performances impossible. It ties this wonderful, personal document and their own circumstances as working musicians no longer allowed to work, to those first few months of a period that is set to affect the rest of all our lives. Faded snapshots of a tragic minute, but ones that continue to look great.

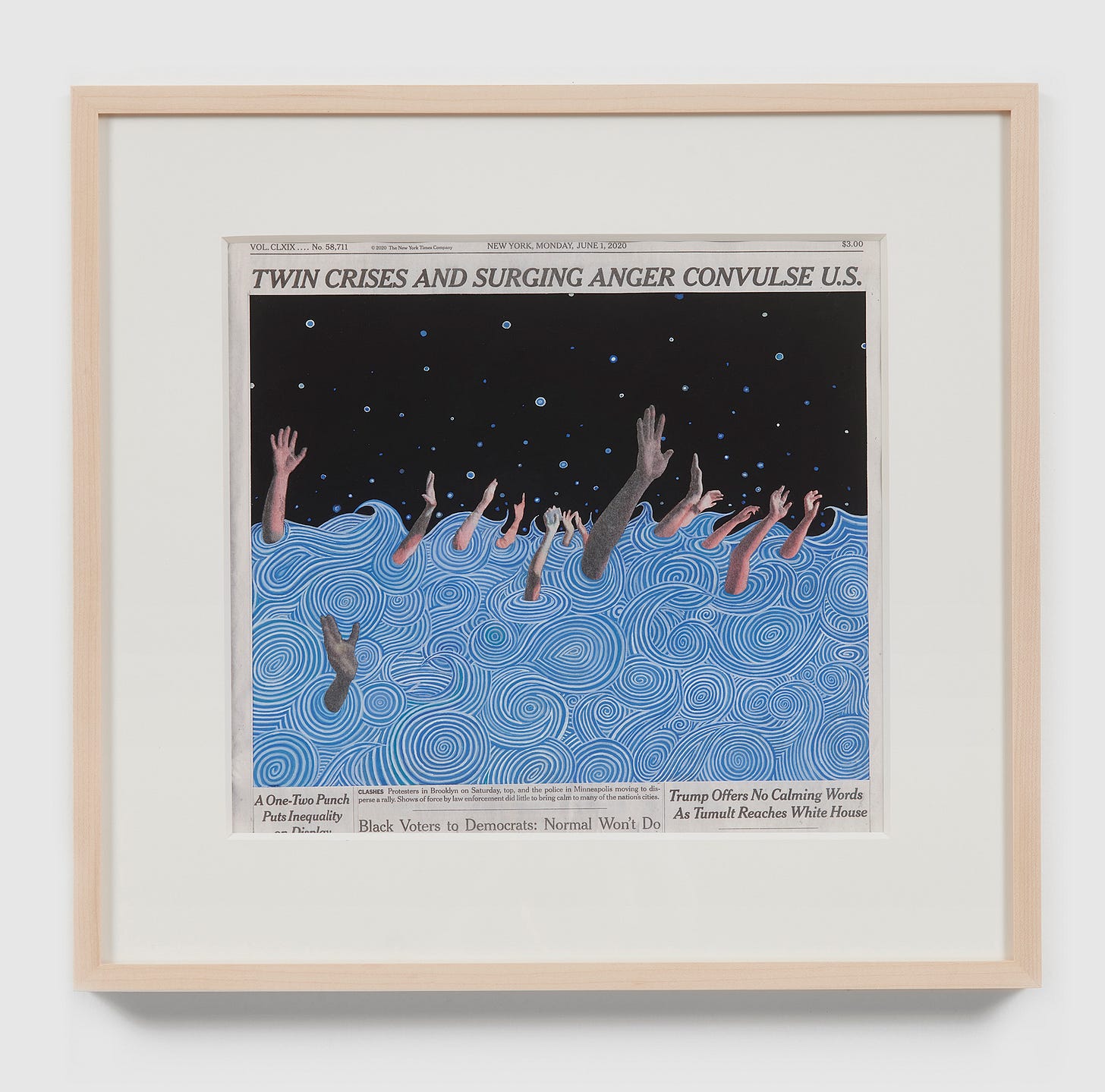

Painter/collagist Fred Tomaselli’s practice already had the platform to engage the so-called news of the day long before 2020 hit its viral stride. The California-born and -raised artist who’s been in Brooklyn for a while now, is best known for large-scale, maximalist, highly psychedelic multimedia paintings which mix natural elements (heavy fauna, some from his garden), all sorts of pills (pre-Damien Hirst), and printed collage matter; these are covered with a sheen of resin, on which Tomaselli paints. (Rock music fans may know his work from a variety of album covers, most prominently the Magnetic Fields’ “i” and Phish’s Joy , and an art-book he made with the members of Wilco.) But in 2005, Tomaselli started a new practice: using the front-page of the New York Times for smaller, quicker, in-the-moment pieces, applying his hallucinatory outlook — part escapism, part reframing of the world through the windows of perception — to not just comment on the day’s events, but media’s coverage of them.

The show currently on view at James Cohan Gallery in TriBeCa collects Tomaselli’s New York Times covers of 2020 — starting with the onset of quarantine in early March, and ending with RBG’s death in September — pairing them with big canvases he created over the same period. (And which themselves include teletype-meets-Burroughs/Gyson-style-cut-up transmissions from Times stories, placing a tripping stenographer’s perspective on the year.) Abstract hues color the real dates and deveelopments, affirming, in the words of essayist Tina Ryan, “art’s importance as a way of understanding and reimagining reality, including its horrors,” and foregrounding the work’s relationship to what’s goin’ on.

Tomaselli’s Times collages keep the headline and masthead as framing devices. Yet he not only adds colors to vibrate, break open and hyperleap narratives into less strictly realist directions, but further subverts the authenticity of news, inventing subheds and secondary front-page stories to reiterate his broader points. (Especially on the subject of climate and ecology.) On some level, his collages are as much first-hand 2020 ballads as rap freestyles recorded at the uprising’s frontlines (see Lil Baby’s “Bigger Picture”). Except that Tomaselli isn’t a reporter but a magical-realism essayist, with no use for the pretend objectivism of the “paper of record,” emphasizing instead truth gained from coincidence and engaging the world behind the veil, where symbolic visions serve a long-range purposes, while time flows in different increments and directions. Here the masthead’s dates, their supposedly logical and unwavering forward march, are evidence of linear time’s inaccuracy.

Because, let’s face it: who of us is going to forget that in 2020, the idea of directional progress through incremental, evenly spaced, widely agreed-upon information gleaned from clocks and calendar, became distorted to the point of disorientation? In 2020, time galloped and crawled at the same time. It almost seemed to stop, just like the world did, in March — and then again in November — only to resume its quickened pace. Waiting for the art to catch up with it, and reflect all that we lived through, feels like one kind of hope. Or at least a way towards understanding.

Dezron Douglas & Brandee Younger’s Force Majeure drops on International Anthem on December 8th. Fred Tomaselli’s 2020 work is on-view at James Cohan Gallery in Manhattan until November 21st.