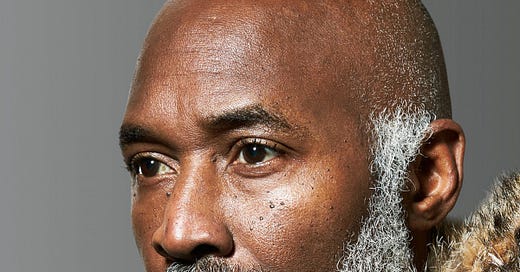

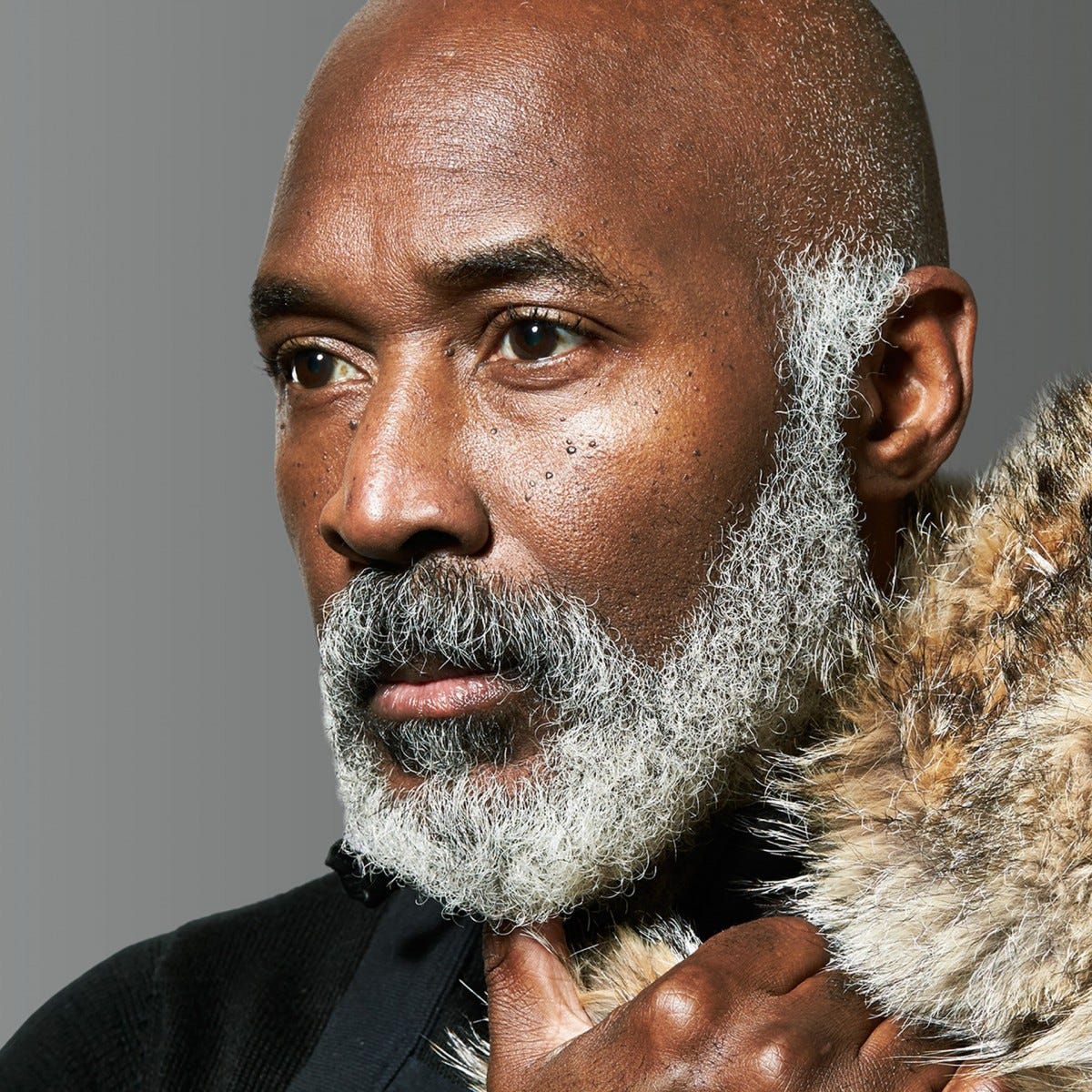

Nick Cave on the Importance of House Music Liberation

In a previously unpublished 2018 conversation, the multi-disciplinary Chicago artist explains how he's been deeply inspired by his dance-club experiences, and why it’s important to keep going.

Rhythm, dance and ceremony have long been embedded in Nick Cave’s work. After all, before he became a multidisciplinary artist — not the dour Aussie singer-songwriter, though I always love an opportunity to point to my favorite quasi-paparazzi snap of all-time — Cave studied at Alvin Ailey, and his most celebrated pieces are called “sound suits,” which often exhibit as part of a choreographed performance. But in 2018, when the Chicago-based artist brought a dance-presentation-cum-party called “The Upright”/“The Let Go” to the Park Avenue Armory, the ingrained affect of club culture and house music on his work became obvious. For some. “The Upright” was the main “art” event, a choreographed narrative that’s also popped-up in non-traditional arts-halls and warehouses around the U.S., in which dancers changed into sound suits and underwent a spiritual and social transformation, breaking the fourth wall in a space designed to evoke the club - if not, the rave. “The Let Go,” which took place immediately afterwards, may have been a familiar art-institution experiential marketing activation — audiences were invited into the designed space to dance as guest DJs played party records — and yet the very choice of those DJs at the Armory (house titans like Marshall Jefferson, Joe Clausell, Tedd Patterson, among others) seemed on-point in a way that institution marketing departments are rarely capable of being. (It was that Park Avenue Armory stand which initiated my desire to interview Cave about dance music and the club, and the conversation below took place in its immediate wake.)

In 2022, the influence of dance culture on Cave’s work is more open, less secret. “The relentless vigor of Chicago’s house music” is cited right there on the wall text that introduces Nick Cave: Forothermore, the artist’s career retrospective currently on view at New York’s Guggenheim Museum (through April 2023). And while documentation of “The Upright” is sadly not part of the retrospective, the show does include a pair of videos that feature elements Cave identified in our conversation as reasons for his continued engagement with club culture. One is a raggedy 1989 black and white directed by Stephen Hamilton called “Nikki” that follows Cave’s transformation from a male-identifying persona into a female, while Nick tells biographical and personal stories, and the music of Steve “Silk” Hurley (among other dance producers of the time) plays in the background. It feels like a loving, lo-fi, art-school preamble to Paris Is Burning. The other is a high-fidelity digital art-video from 2012 called Blot, featuring one dancer in an all-black, fringe-layered sound suit, moving in a split-screen, an effect that makes the dance appear to be an animated Rorschach test, with experimental sonic design (FX’d ocean waves) that could pass for the noises the suit itself is making. Here then are aspects of identity and imagination, movement and abstraction, change through movement, transformation through trance. The club as a complicated place of full-bodied release.

I was very familiar with Cave’s work before the phone conversation that took place on that July 2018 afternoon — at one time, my wife worked at the gallery that’s long represented his art, and we never missed an opportunity to check out what he was up to next. But it was seeing, and being deeply affected by “The Upright” which made me want to quiz him about his “club life” directly. I was hoping to turn it into a piece about how music (especially dance music) was permeating into the work of numerous contemporary artists. It’s an idea that’s only grown stronger in the intervening period. Some of the things that Cave and I discussed back then have come to fruition. Others are in the process of. I kept all the contexts, but edited the conversation for clarity — you can tell that Cave’s contemplative phrase of choice is the hesitant “sort of,” I extracted quite a few of those.

I did cut the opening exchange about my being stuck in Chicago for a period between seeing “The Upright” and when our conversation taking place. That initial back and forth did elicit one great note from Cave, after which I pretty much knew we’d have a cool conversation. “You know,” he said, “Chicago’s always had this sort of music infrastructure that has really changed the face of a lot of music…that I’m interested in anyway.”

Indeed. Thank you Nick Cave!

What I found in “The Upright” and “The Let Go,” and some of the events that were scheduled around the Park Avenue Armory performances was a manifestation of house music culture in an art space, work that pulls from that culture, and expresses that culture, for those who will recognize it being there. And so I had a strong inkling that I wanted to talk to you about house music and club culture because it seemed from this work that you were deeply familiar with it. You grew up in Missouri, but you studied at Cranbrook [Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, just outside of Detroit] and you've been living in Chicago for 25-26 years. What is your engagement with house and club culture?

I studied at the Kansas City Art Institute doing my undergrad study and then at Cranbrook. But there, you know, [we had] Detroit. I don't know if I would've survived Cranbrook without Detroit. But let's go back to the late ‘70s, when I was at the Art Institute in Kansas City. It's really sort of like if music has always been this spirit that allows me to be liberated. I'm one of these individuals that would go to the club and I would walk in the door, I would hit the dance floor, and I would exit out the door. I really didn't know anybody. It was my refuge. It's what saved my life. I used it as therapy. It was how I was able to work through ideas, and it allowed me independence without judgment, you know? That space today doesn't exist. I'm like, where do these kids go and, like, fucking let it rip? [The dance-floor] has always been this force that has allowed me to empower, to stand on my own, and to sort of validate my confidence, reassure my confidence. It started out as disco, which then led into house. But you know, it's always disco. Then it was disco that had that sort of a tribal soul sound, rooted into more of a, I would say, bass and drums, a little bit more primal, [which] I found myself moving towards. And then, you know, when I went to Cranbrook, in order for me to even sort of stay balanced, I had to be in Detroit.

And did you go to, like, Club Heaven, Music Institute, those kinds of places?

Exactly. And it was these underground clubs that were just like…Thank Jesus, Lord, that I had <laughs> these venues to kind of go and like, just let it rip, you know? I'm like forward thinking, forward dressing, and those spaces allowed me to be my authentic self. And the importance of that and knowing that, is what fuels the fire, for me to address and to be dealing with social injustice and political issues around race and gender. It was these places that were safe. And then I found myself moving. What really kind of sealed the deal for me is when gospel house started to come into the equation, because I think spiritually I was already operating from that place because I'm telling you, there would be moments I would be out on the dance floor… Like here in Chicago, I would go to like, Generator. What were some of the other places?

Was The Warehouse still open?

Warehouse, Buddha Lounge back in the day, these places where I would get to the point where I would be just rocking it out, that I could literally have these out-of-body experiences. I would be present, grounded here, but I could see my spirit there. And so for me, that's really what it was about. It was about these spaces, these places that allowed you to not be intimidated, allowed you to sort of release however you needed to. And it was all just through movement, in response to music that was just phenomenal.

Before we continue, you said that it started in Kansas City. Do you remember any of the club names in Kansas City when, uh, when you were at the Art Institute there?

Oh my God. I would go to like…Dover Fox was one. There's the club in Westport, I can't remember. Dixie Bale would be another one. And these would be clubs that were like…they would never like these sort of, let's say, corporate clubs. They were always these fucking holes in the ground <laughs>. But there were just these amazing DJs. There was one particular DJ named Mark Nelson that literally lived maybe a block from where I lived. He would pretty much call me like, “Nick, I got some new, new music. I want you to come in and hear it.” Me and my few friends from the Art Institute, we would almost be like, his test. He would test all this music and we would respond to it. I would close the club with him, and we would just walk home and just be talking about music. So that was very, very interesting too. Remaining open, because I think back then music was evolving in so many different facets that you had to remain open in order to allow different genres of music to enter the equation. But I think music, fashion, design, art — it was all kind of linked together. It was all this sort of interesting world that was open to independence, freedom of expression, free spirit. And so it allowed all of these vast art disciplines to interface.

You were studying to be a visual and a tactile artist, and you were obviously a dancer. Did you have any desire to possibly study music and pursue it? Or did you think that, by that point, you were already engaged with it in a different physical way, that its influence on you was already settled in one way as opposed to in another?

It has always been part of my practice. But I've never been interested in pursuing music as a pathway, but it has always been incorporated within what's my art-making. May it be through either performance or fashion. I think those were the two sort of parallel pathways that informed and added another dimension. So I've always been interested in it in a collaborative sense. And I think, as one who has studied dance and just movement, I think music accompanies that in many facets.

Tell me a little bit about these ideas, these freedoms that you learn on the dance floor. As I was watching the upright, the ceremony of it, the release of it at the end, the gospel chorus that accompanies the whole thing. It really was sort of an expression, a thinking of the dance floor as like a place of cleansing. Can you tell me a little bit about how the ideas of freedom and release that we find on the dance floor are initiated in or inform what happens in “The Upright” and then in “The Let Go”?

For me it's this sort of strange rite of passage. I'm just thinking about clubs, and then I'm thinking about… OK, let's just stay with the club for a minute: I'm at the club and I'm with friends, people I know (or not know). And let's say somebody's doing cocaine. And I'm like, why am I just sort of passing the tray? Why aren't I indulging in that? And I realize that I don't need that in order for me to establish a high. And that high for me is independence.

Independence was for me the ultimate sort of freedom. Free to be expressive in an environment that didn't judge. I mean, I would think about even just dressing. I'm thinking [on] Monday, like, “Okay, what am I gonna make to work the club?” Because that was just part of the dance. It was your arena, it was your platform, it was your stage, it was your performance space, it was your display.

And so all of this is the same with “Upright.” “Upright” is the rite of passage. It's stripping down one's own identity and leaving that on the stool, and then rebuilding one's selfhood in this way that it's all based around this sort of extreme opulence, fabulousness, and this sort of extreme positioning and parading and adornment, and it's really how I feel sometimes. It's really what motivates me and keeps me at a particular place in my practice, because you know what? As an African-American male, I am surrounded by a lot of disparity, based on the climate today. But I have to also understand, that's just part of my existence. I don't have a choice, but what I do have is the ability to inform my being that I am everything, and can be everything.

That's really what “Upright” is about. It was this rite of passage. It was really breaking one down, building one’s self-hood up to face all obstacles out in the world. As you know, in “The Upright” the garage door at the back rises up [at the end of the performance] and then [the performers wearing Cave’s Sound Suits] proceed to go out into the world. So it's all about empowerment.

And is it fair to then say that a lot of that is what you described to me earlier, these notions that you felt on the dance floor earlier in your life directly inform this work?

Oh, yeah. It was the place where… I didn't necessarily always have someone to go to, to express my feelings. And so, I'm like…”Well, how do I do that?” Like, what is my mechanism? What is my speed? What is my fuel? What is my intake? Where is that place where I can negotiate and express myself and get a reading of myself based on the environment that I'm surrounded in? So, I don't know where I would be without it. I have no idea.

At this juncture in my life, I think of it as being part of my DNA.

Exactly. <laughs>

That's fantastic. I am happy that I intuited correctly.

And you know, the thing that's amazing, what you're providing me is that translation. It's like I'm creating this sort of expression, but then I'm also interested in how is it being received, how's it been translated? Are we connecting in ways that are informing us to understand how we need to proceed, and how do we give ourselves permission to exist fully as our being in the world? How do we become of service in the world?

You know, I was trying… I was creating an environment that allows us to transform ourselves in a moment — to be in the moment, to be surrounded by and chased by this enormous streamer curtain that was occupying and moving throughout the entire Drill Hall. That was me in a sort of dream state, thinking about Studio 54. What did that feel like? What was that sort of mood? How it was bigger than life, because these clubs made you feel bigger than life. They just sort of forced it out of you, a different way of existing. [As I said,] I was able to carry on my week, I was able to go and work it out. So again, it was about empowerment. And that's how music always sort of informed my life. It has allowed me to… I don't practice any particular sort of religion, but I am very spiritually connected to something greater. In some cases it's in the club, in some cases it may be in my closet — who knows? <laughs> — or in my studio as I'm working. I mean, it's not… It can't be defined.

It's not a formula. But it is something tangible.

Totally. And, you know, you're lucky if you're able to… How do you give yourself permission to let go? How do you do that? That's what moves us forward. Two things do that for me: to sit in silence. I do that every single day for like an hour, maybe three. I've been doing it for three decades, as long as I've had a studio practice, you know, always been alone. I've always been making and tearing up and going through it because it has allowed me to come face to face with my truth. And that's the same thing that happens on the dance floor. I have two choices. I can get out there and I can sort of be part of the mainstream and fit in. Or I can like say, fuck it, I've gotta let it rip. It's an out-of-body experience. I have to be aware and I have to respond. I have to live in my authentic self. I can't do it any other way. With that being said, you find that in some cases it's a lonely road. But I'm everything that I can be today, based on me paying attention to what my body needs, and how it needs to express itself.

Do you still go out to the club much?

If I can find one. <laughs> I mean, I'm not one for going out and hanging out. I don't drink. But let me tell you like when they have here in Chicago the house music in the park, the Chosen DJs in the park…I am totally there. As I said, I just go, I ride my bike, park it, lock it, and I'm totally on the dance floor. I'm all about it because it's like a rarity right now, I think. We just don't have these spaces anymore. The whole club scene has changed, I think. There's not the club anymore, as opposed to individual hosting, uh, events here and there.

And so I just purchased a building here in Chicago. Me, my brother who's also in the arts, and my partner who is an amazing graphic designer and product designer. And so we are, we have created this space, and there's one particular part of the building that is sort of about 3000 square feet. Ohhhh, trust me. We will definitely be hosting a number of dance parties. That's what we're doing. It's gonna be a project space where we’re just going to be creating opportunities and experiences.

We're just in this sort of extreme changing time, you know, nothing's forever. So how do you sort of host these amazing moments to bring us back to a place?

So that's interesting that you, that you say this. I was in Chicago to interview the artist, Theaster Gates. And part of the reason I wanted to talk to him is because at his Stony Island Arts Bank, he's creating this archive, part of which is Frankie Knuckles’ record collection, which is another way to try and archive these moments, right? On the one hand we can archive Frankie's records; On the other hand, we can't really archive the moments of magic that those records helped bring to life. The best thing that we can do is create a library of the tools with which he worked. And part of the reason why I wanted to talk to him is this idea of trying to collect a memory bank of work that is ephemeral, the magic that a DJ creates on the dance floor is created and then gone. It's something that you only carry within yourself.

It also asks the question of how you archive popular artistic experiences nowadays. Recently, my wife and I went to see a Raymond Pettibone exhibition, and Ray drew so much, made so much work, that to truly archive all he did, considering how much of it early on was, like, punk rock flyers in Los Angeles…a full archive is kind of impossible. So it's interesting to hear you say that you're creating an art space where the art aspect — the magical art aspects of these moments, these experiences — can be created. To me it's almost like the club as a museum, but a museum of things that happen in the now, rather than things that hang on walls or something.

Exactly. And also, what does that look like? It's not just the music, but what does it look like? What does that look like in terms of who's there, what are they bringing, what do they do? And just that right there sets the atmosphere, creates the ambiance. That then the music becomes the framework for all of us to indulge in this sort of high level of creative empowerment. And that's what I'm interested in. Because I know what that moment was like for me, the importance of it. There's still a lot of amazing creative people that still have no place to go to feel liberated. And so, how do you create those spaces where, you know, we look different, but it becomes this collective, it becomes common ground. And it's not about recreating, it's about what does that look like today?

Absolutely. This is not a nostalgia moment.

No, no. And to be able to sort of host… just thinking about Frankie Knuckles collection, you become the host that's presenting this work. And that work… Music has a partnership with the body, and in order to understand its power, it needs to identify that power through movement. And so, you know, I'm hoping Theaster at some given point, every other year (or whenever), will host the Frankie Knuckles collection and create a fabulous happening. Because otherwise we've got all this music stored, but nobody's hearing it.

We have to remember that music needs a partner in order for it to make sense and in order for us to provide it with the message that it's giving us. It's a call and response. How do we respond to it? And it's not only the music, but also the DJs. It's interesting when you talk to these DJs, they are sort of identifying how they are going to program the evening based on what's happening on the dance floor. Because I know that when me and my friends from the Kansas City Art Institute, maybe a pack of eight of us, and we were just fucking crazy back then. The moment we would hit the club, the DJ was like, “Oh shit, the crew's here.” And so that was, he would then start to orchestrate his entire program for the evening. It was cute at the beginning, fun before we got there, but when we got there, he was like, oh shit, I gotta turn it up. <laughs>. But that was really kind of, again, this call and response. It's like, you know, you need your crew there, in order for you to, like, hit it. That's what brought them joy and it validated their purpose.

It's how they were recognized and validated, it was through the audience that accompanied their work.

So it's interesting how ideas of collaboration, the role of responsibility, the foundation and the infrastructure dictates what happens within a space. And yet we are all instinct and we all are dependent on one another in this sort of amazing, magical way.

You know, it's like going to the club. It's like, yes, I may have dressed to a certain extreme, but I wasn't the only one. So, you know, just the sort of dependence on your surroundings that allowed you to be expressive, and to be able to have that sort of platform and sound that also provided the ambience and the sort of aura in the room was like… Oh my God, it saved my life. I swear to God!