"My Name Is My Name" - some thoughts on Prince

Retro Read: a piece from 2016, in the shadow of his passing, as parenthood flourished and professional personhood plateaued, on the idea of acquiring a name in a land where it means everything

On the occasion of the anniversary of Prince’s unexpected passing, here’s a piece I originally published on May 11, 2016 on Raspberry Fields, a Tumblr that was a less-focused precursor to Dada Strain, and whose title was based on my creative-projects name, Raspberry Jones, which was indeed a nod to the man. Read on. It’s a personal essay, sure, but it’s stood up pretty well not only as an intimate reflection, but a nod to cultural conversations still under way. (I’ve copy-edited the original piece, but it’s about 99% the original.) Prince was an extremely important artist in my life, a constant musical companion, ever since I saw the video for “Controversy” on America’s Top 10 in 1981 or ‘82. More importantly, he was present when I was learning who I was and what I believed in, whether the topics were sexuality and race, art and spirituality, or the nature of politics or of musical genre. One ever-present lesson I took from his career was that it was OK to change your mind and your direction, that what felt utopian one moment, can be infernal at another, but that having a code of ethics attached to how you operate was…crucial.

By early evening on the Thursday that Prince died, with professional obligations fulfilled and obituary deadlines met [ed. I wrote a day-of remembrance for Vevo.com since lost to the Internet], I finally gave in to a need and started sobbing my own personal purple tears. This, of course, required an appropriate soundtrack, and like many around the country, I tuned onto The Current, Minnesota’s public radio station, which was serenading the nation and the world, reflecting on the loss of a person many regarded the most gifted musician of his generation. It was a surreal moment — one of those increasingly rare and unexpected events that seems to actually unite everyone in a single cultural conversation, in which the deviations of individual memories are not a slipstream’s (or social media feed’s) white noise, but actually the filling out of a scene. In this case, fade to purple.

At some point the disc jockey opened the lines to solicit local Minneapolis listeners reminiscing about Prince Rogers Nelson, and who should call in to express his grief but Tommy Barbarella. A New Power Generation keyboardist in the late ‘80s/early ‘90s, Tommy was never among Prince’s better-known sidemen, though he does get a prominent shout-out on the long version of “Sexy MF” right before playing a rolling organ solo. Barbarella was as shell-shocked as the rest of us, and the exchanges reflected as much. Yet before escaping a conversation one could begin to hear he wasn’t emotionally prepared to have, he did say something that seemed at once obvious (if you’re up on your Prince mythology) and penetrating.

“You know, he gave me my name,” said the man born Tommy Elm. “He named me.” Barbarella certainly could have been speaking metaphorically — as in, “playing with Prince gave me a career,” which it did — but you also knew he damn well wasn’t. In one phrase, he related to the global grieving with an anecdote, a metaphysical narrative, and personal insight that sounded like the emotional abandonment of a lost child coming to light. It is a powerful act to bestow a name upon someone; but it is also a privilege to accept such a gift consciously, warmly; and even more so, to be able to confront the short legacy of your name in order to subvert it in your own image. (Or tailor that self-image to the name.) The naming mechanism is pregnant with connotations of parenthood; but it’s also a benevolent blessing from figures of stature or members of a court. Being a musician who gets named by Prince was approval not just from royalty, but from widely acknowledged genius; sure, you could have tried at one point to downplay the meaning of bequeathed stage-names, but it's harder when the entire world has one for it’s screens, and cultural identity works as currency. Few common social acts are more primal, or more deeply ingrained in our DNA.

So it was unsurprising then that as Barbarella testified on The Current, I could relate to him on any number of levels. The most obvious being the sudden realization that Prince had given me my name too. Or, more to the point, I took it off him.

(The following then is the one-time-only telling of the not-even-that-interesting-but-somewhat-timely Raspberry Jones creation myth.

It’s Spring 1991. I am writing for The American University’s student newspaper, The Eagle (music reviews, natch), and one of the things I get assigned to write about — actually, I probably jostled for it — is Deadicated, the first comp of mostly crappy Grateful Dead covers by artists both likely and un-. Among the most disappointing of the 15 tracks is a sanded-down, bar-band reading of “Casey Jones” by Warren Zevon (co-starring David Lindley and a bunch of LA sessions dudes). The disappointment stems from the coupling of good musicians full of feel for the material (Zevon and Garcia had a long-standing back’n’forth, the Dead’s 1978 cover of “Werewolves” onward) with a lazy arrangement of a song whose arrangement really wasn’t looking for help. What makes it worse, is that it’s an inferior version of a move Zevon pulled off much more successfully a couple of years earlier, when, billed as the Hindu Love Gods (a one-time, drunken electric hootenanny with members of R.E.M.), he covered “Raspberry Beret” as a sanded-down bar-band stomp. Released as a radio-friendly lark in ‘89 or ‘90, this “Beret” was no one’s idea of genius, more like an in-the-moment curio which somehow chose not to age, and whose fun barely diminished on repeated listens. The Dead cover, on the other hand, oozed studio-musician time and money, with the lark turning into lowest-common-denominator product. Writing about it for The Eagle, I said as much — stating, in fact, that this version wasn’t “Casey Jones” so much as “Raspberry Jones,” and even that was giving it too much credit.

The phrase stuck in my mind. God knows why I thought I needed a nom de plume at the time – except that there was a lot of rap music, and DJ names in the air – but I did instantly think it a good one. I enjoyed that it sounded like a play off a blues-man’s name, and that it mirrored Pink Floyd (itself derived from the name of two blues players), and that it sounded hippie (which I very much was at the time). Maybe best of all, I liked that it was 100% American in a way that Piotr Orlov or Peter Orlov was never ever ever going to be. It has traveled with me ever since.

Now, it’s a quarter of a century later. The men whose musical inspirations pushed me to mash together the titles of their compositions into a moniker I’ve used my entire adulthood as a personal creative outlet, have died. And as Barbarella spoke, I wondered: What’s in a name? In receiving one, choosing one, choosing to change one, and bringing forth meaning with that choice? Naming something or someone is a radical act of assimilation and dissimilation, full of preferred results, unintended consequences, and endless reactions, as playful as a romp in the sunshine, or as serious as your life. It’s saddled with historical meanings and symbolism — especially in America, where plantation owners and Ellis Island clerks destroyed familial identities of everyone in their purview. But here, it’s also a matter of choice. Whenever I think of the socio-mechanics of names, I think of the original Conquest of the Planet of the Apes, and the scene in which the ape that will grow up to lead the rebellion against human race and change the world, is asked to choose his own alias; he picks “Caesar.” These are opening lines in grand narratives, fables and otherwise.

Only upon Prince Rogers Nelson’s passing did I discover that he got his birth-name from the group his pianist father played with, the Prince Rogers Trio. The very notion that music creation was an inspiration for it feels more than just beautifully direct symbolism of the man he became, it speaks of the value his parents ascribed to this creative occupation. The name came with built-in bonuses too: It did not simply foretell nobility but presented the young man with a natural palette, one he used all his life. And as a pure, linguistic one-word signature it bested — with the possible exception of Madonna, another remarkable parental decision — the monikers of all of that era’s other forename-identified pop giants. Even someone without a complete command of the English language, much less a comprehensive understanding of the nuances that could be brought to the word “crucial,” saw it as special and intriguing from the get-go.

Of course there was much more. In 1992, less than a year before Prince changed his name to what he called a “symbol of love” (a figure that mixed the astrologically-derived gender symbols for male and female with a regal trumpet-like shape, that had its own creation myth), he released an album with that very symbol for a title. He’d already been playing around with the nature of his own identity as personified by specific characters — Camille and Spooky Electric were at the center of his greatest creative period, spanning the released and unreleased work of 1986-89. Except that the Love Symbol album, which essentially forecast the nameless era, opened with a straightforward declaration of self, which carried the emphatic title, “My Name Is Prince.”

The song was not among his best — even as a statement of personal intent, it was no “Controversy.” At the time, its primary raison d’etre seemed to be Prince’s then-constant flirtation with wanting to strike a realer-than-real hip-hop pose (hence its sub-Rakim-ish verses by NPG’s Tony M). But that wasn’t the tune’s entire trip. “My Name is Prince” eschewed the contradiction of who he’d been for more than a decade in favor of ideas about personal integrity, who he was now and who he was on the verge of becoming. The song begins by running through a sampling of previous hits and the re-establishment of some basic tenets of Prince’s duality, before diving into a description of the future, predicting his deeper turn towards religion (not just spirituality), while undercutting both the messianic self-seriousness and creative/professional aspirations he was long accused of by the media. It’s especially interesting that this, one of his last acts under that family-given name, was an oultining of personally profound truths he seemed to live by, til his dying day.

Then of course, things got surreal. In the context of its contractual value, in the historical face of how generations of Black Americans first received “their” names (with the word “Slave” written on his right cheek, should you miss the depth of what he felt was the backstory), Prince’s family-given name became an albatross of contractual circumstance. The fight over releasing music through Warner Bros., his label since 1977, under that name began soon after he signed the mega-lucrative deal with the music corp, and the artist’s self-renaming so radical, that even long-term critical allies began to excoriate him for what they saw to be impudence. The very simple act of what to call him in public became a discussion topic, with the agreed-upon moniker, The Artist Formerly Known As Prince (TAFKAP), only reinforcing previously known absolutes, and pushing those unsympathetic to his plight even further away. (Compounded, of course, by WB releasing product the Artist only tangentially had a hand in compiling.)

The historical perspective frames the episode as less of a Page Six-meets-Late Night monologue kerfuffle, and more a conversation of how cultural legacies are built and exploited in America — especially when the culture-makers in question are Black, and the moneyed interests are far less likely to be. It was a modern-day variant of “What would you give in exchange for your soul?,” with the devil’s blue-eyed visage and the cut of his suit retaining a strange familiarity. (It was, then, heartening to see that in the wake of Prince’s death — and as I was adding final edits to this piece — the Minnesota state legislature has proposed the “Personal Rights in Names Can Endure” Act, aka PRINCE Act, to stop the unapproved exploitation of a creator’s name. So download those YouTube clips now, brothers and sisters.)

Still, neither the public litigation nor the stale punch lines told the whole story of the Artist’s relationship to his name — and to people’s relationship with his name — during the TAFKAP period. As always, the nuanced anecdotes were far better than the tabloid narratives. A week or so back, during a great “Remembering Prince” roundtable at NYU, the journalist Toure told a story of playing basketball at Paisley Park with the Artist, while doing a cover story for Vibe during this unnameable period. In short: Toure throws an errant pass that’s headed towards the Artist’s head but which he-who-(at the time)-can-not-be-named doesn’t see; the journalist wants to warn him that the ball is headed for his noggin, but…he has no idea what he’s allowed to call him!!! The Artist’s reaction, as Toure tells it, is exquisite in both its self-awareness and his humanity. It brings to mind another thought, the recognition that when one’s name, a title given to essentially one’s soul, is difficult to comprehend, it becomes a reason to harden, to develop a sense of humor, or to go Zen. Prince Rogers Nelson did all three.

It’s a thought that I can also kind of relate to. My own name has changed a couple of times, through language, cultural transformation and context, but also due to my own self-reflection of who I am. The Social Security card issued in 1977 said “Piotr,” but that kid, hell-bent on Americanization, quickly found himself crushed under the consciousness of its perception, and changed it to Peter, before an experience in St. Petersburg, on his first visit back to his homeland as an adult, slowed down the charade of pretending to be something he…I could never be. Because I have little creative genius to fall back upon, I’ve tried to make it easier on those around me: “Call me Peter” is inevitably among the first things I say to people who have only seen my name in writing. It is an act —but not — because I have absolute comfort with the character and the self that it represents.

Just as I do with Raspberry — or Mr. Jones, if you’re nasty. I still clearly remember the moment when I chose to use “Raspberry Jones” out for the first time, soon after its birth. It was as a byline for The Eagle (again), this time writing a scathing review of U2’s Achtung Baby that I would probably take back 100% had the editor not refused it initially (bad writing, bad critical thought), while also decrying my “ridiculous” pseudonym. Nevertheless, I do remember the consciousness of choosing that name, and, if I am being a little melodramatic, of the feeling that it was choosing me.

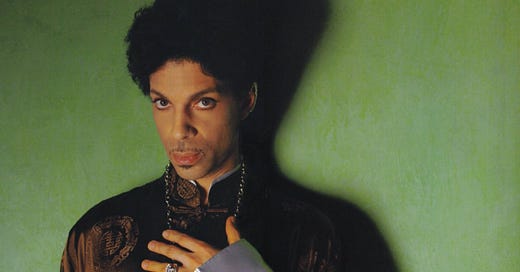

(photo of Prince by Afshin Shahidi, a friend at The American University who, during the Aughts, became The Artist’s photographer. Fun fact: Afshin still has the VHS copy of Sign o’ the Times movie he borrowed from me during the first Bush administration.)