Dada Reads_121120

Articles: Lauren Michelle Jackson on Dolly Parton, Ferris Jabr on "The Social Life of Forests," Liz Pelly on Sp*t*fy, Ford Foundation's Creative Futures, Other Inter on the Value of Squads, and more

An occasional list of some recent recommended texts that imagine the future, reappraise the past, and give full-hearted critique to the here and now. Music, sociology, ecology, technology, community.

Lauren Michelle Jackson, “The United State of Dolly Parton” (The New Yorker 10/19/20). There’s been a ,few great Dolly reads of late (see also Emily J. Lordi’s piece in Times T last week), but Jackson’s essay lays out a wonderful pro-Parton argument around a “review” of Sarah Smarsh’s book, She Come By It Natural. “The particulars of Parton’s life story are grafted onto those of white working-class women who, like Parton, might never see themselves in feminist discourse but have been ‘living feminism’ all along. These are women tested by poverty and patriarchy, who do what needs to get done and escape when it’s time, even if the fleeing lands them in another bad situation that they’ll soon need to escape. They’re women who are wronged (“Dagger Through the Heart”) or possibly doing wrong (“I Can’t Be True”), finding a soundtrack to their own loves in “Love Is Like a Butterfly.” They are Parton’s muses, with lives resembling the main characters of her jubilant and sad-ass tunes. Parton is a genius, but all those stories come from somewhere. And, though Parton left and made a mint, the women she might’ve been kept on living. They understand Parton like few can, and, for the most part, their contributions to progressive consciousness have gone unsung except by Parton.”

Karen Hao, “We read the paper that forced Timnit Gebru out of Google. Here’s what it says.” (MIT Technology Review 12/4/20): Last week, Timnit Gebru, the co-lead of Google’s ethical AI team, was forced out of the company, claiming that the dismissal revolved around a research paper she was co-authoring. The issues the paper brings up regard not only the future of artificial intelligence but global expenditure, equitability, and the nature of the kind of world in which we want to live. “The paper presents the history of natural-language processing, an overview of four main risks of large language models, and suggestions for further research. Since the conflict with Google seems to be over the risks, we’ve focused on summarizing those here. 1) Environmental and financial costs: Training large AI models consumes a lot of computer processing power, and hence a lot of electricity. Gebru and her coauthors refer to a 2019 paper from Emma Strubell and her collaborators on the carbon emissions and financial costs of large language models. It found that their energy consumption and carbon footprint have been exploding since 2017, as models have been fed more and more data….Gebru’s draft paper points out that the sheer resources required to build and sustain such large AI models means they tend to benefit wealthy organizations, while climate change hits marginalized communities hardest. 2) Massive data, inscrutable models: Large language models are also trained on exponentially increasing amounts of text. This means researchers have sought to collect all the data they can from the internet, so there's a risk that racist, sexist, and otherwise abusive language ends up in the training data….The researchers point out a couple of more subtle problems. One is that shifts in language play an important role in social change; the MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements, for example, have tried to establish a new anti-sexist and anti-racist vocabulary. An AI model trained on vast swaths of the internet won’t be attuned to the nuances of this vocabulary and won’t produce or interpret language in line with these new cultural norms. It will also fail to capture the language and the norms of countries and peoples that have less access to the internet and thus a smaller linguistic footprint online. The result is that AI-generated language will be homogenized, reflecting the practices of the richest countries and communities. 3) Research opportunity costs: The researchers summarize the third challenge as the risk of “misdirected research effort.” Though most AI researchers acknowledge that large language models don’t actually understand language and are merely excellent at manipulating it, Big Tech can make money from models that manipulate language more accurately, so it keeps investing in them. Not as much effort goes into working on AI models that might achieve understanding, or that achieve good results with smaller, more carefully curated data sets (and thus also use less energy). 4) Illusions of meaning: The final problem with large language models is that because they’re so good at mimicking real human language, it’s easy to use them to fool people. The dangers are obvious: AI models could be used to generate misinformation about an election or the covid-19 pandemic, for instance. They can also go wrong inadvertently when used for machine translation.”

Sam Hart, Toby Shorin, Laura Lotti, “Squad Wealth” (Other Inter 8/19/20): Other Inter is a strategy and research group—basically, an agency that writes “trending” white papers. Hence the language is stilted and forced, and the perspective is heavy towards consumer and market analytics, rather than history and sociology. Nevertheless, they regularly stumble into interesting spaces and foundational current truths. Here, I’d replace “squad” with “community” (time-worn) or “pod” (Covid and post- lingo), and note that a lot of this thinking has been going on in scenes and cultures for a long time. But it certainly feels timely. “Squad culture is the antithesis of neoliberal individualism. Millennials are healing from decades of irony poisoning, rediscovering what it's like to have generative, exploratory relationships with one another. Younger generations are already imbued with extremely powerful squad energy, equipped with formative experiences in Minecraft, DOTA 2, and Fortnite parties. Whether bound together for survival or for LOLs, the squads formed by today's crisis will be resilient. Distance is no longer a barrier with the closeness of network space—soon vital culture will be predominantly enacted by fictive kin. Group collaboration is now the strong default, putting squads at the center of social, cultural, and economic life. To paraphrase Bill Bishop: today people are born as individuals, and have to find their squad.”

Ferris Jabr, “The Social Life of Forests” (New York Times Magazine 12/2/20): Imagine if nature is not strictly about the “climb to the top” of natural selection, but about community integration. “Since Darwin, biologists have emphasized the perspective of the individual. They have stressed the perpetual contest among discrete species, the struggle of each organism to survive and reproduce within a given population and, underlying it all, the single-minded ambitions of selfish genes. Now and then, however, some scientists have advocated, sometimes controversially, for a greater focus on cooperation over self-interest and on the emergent properties of living systems rather than their units. // Before [Suzanne] Simard and other ecologists revealed the extent and significance of mycorrhizal networks, foresters typically regarded trees as solitary individuals that competed for space and resources and were otherwise indifferent to one another. Simard and her peers have demonstrated that this framework is far too simplistic. An old-growth forest is neither an assemblage of stoic organisms tolerating one another’s presence nor a merciless battle royale: It’s a vast, ancient and intricate society. There is conflict in a forest, but there is also negotiation, reciprocity and perhaps even selflessness.”

Liz Pelly, “#Wrapped and Sold” (The Baffler 12/3/20): If you only read one person critiquing the streaming behemoth, it should be Liz. “It makes perfect sense that a company whose product is fully built on exploited labor would scheme new ways to squeeze more uncompensated value out of its varied user base. To that end, it is worth remembering what you’re advertising when you are doing advertising for Spotify. And that is: a publicly traded corporation with a fifty-three billion dollar valuation that’s only responsibility is to its stakeholders, who are largely investment management firms and major labels (who reportedly make millions per day from streaming)….If we accept the idea that the number of streams a song or an artist is able to amass is a valid way of determining what is important, we are significantly limiting the scope of sounds, voices, and emotional responses that are deemed valuable within music and culture.”

Charles Duhigg, “How Venture Capitalists Are Deforming Capitalism” (The New Yorker, 11/30/20): I generally don’t do hate-reads. But this story of how much money was sunk into WeWork, that organization’s destructive, anti-free market tendencies, and the fallacy of the hyper-funding process that perpetuated its rise, is criminal comedy. Proceed with caution, especially if you are financially struggling, because deep anger may ensue. “A 2018 paper co-written by Martin Kenney, a professor at the University of California, Davis, argued that, thanks to the prodigious bets made by today’s V.C.s, “money-losing firms can continue operating and undercutting incumbents for far longer than previously.” In the traditional capitalist model, the most efficient and capable company succeeds; in the new model, the company with the most funding wins. Such firms are often “destroying economic value”—that is, undermining sound rivals—and creating “disruption without social benefit.”

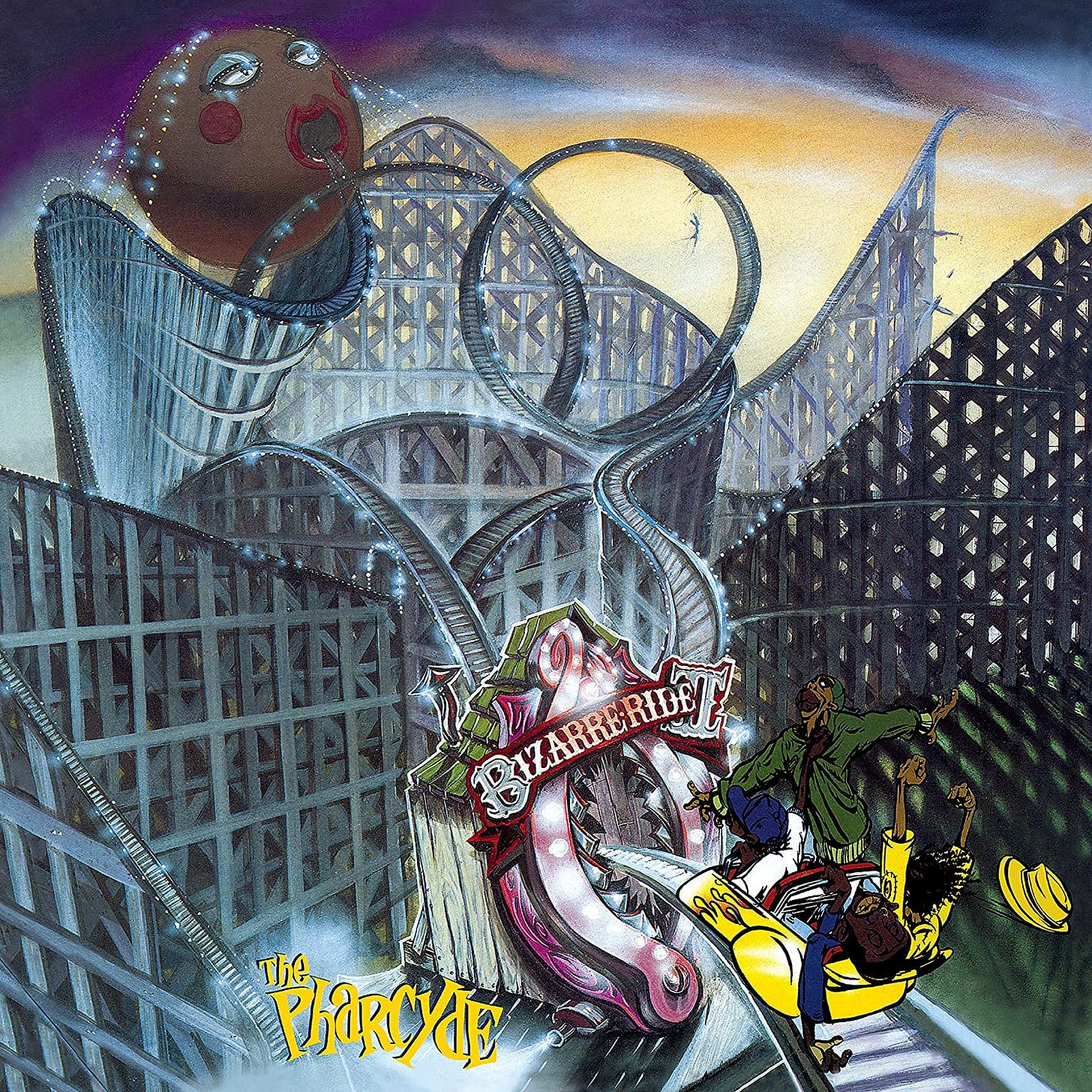

Ross Scarano, “Sunday Review: The Pharcyde, Bizarre Ride II The Pharcyde” (Pitchfork 12/6/20): A deep dive into an under-appreciated classic from the Golden Era. I wore this one out in 92-93. “In a graffitied house near the USC campus of South Central L.A., the original members of the Pharcyde absorbed the eye-popping honesty and absurdity of the ribald albums [Richard] Pryor cut in the ’70s. Holed up at the digs they dubbed the Pharcyde Manor, they worked on their debut album Bizarre Ride II the Pharcyde over the better part of 1992, elaborating on a demo made up of three gems: “Passin’ Me By,” “Officer,” and “Ya Mama.” Pryor’s language, gathered from bits like “White and Black People” and “Black Funerals,” showed up in their lyrics and in the production, sampled from vinyl. He was their spiritual kin. Bizarre Ride II the Pharcyde remains one of the most boisterous and creative acts of adolescent knuckleheadedness and confession in hip-hop history. The album, released in November of 1992, is as much the product of the Black comedic tradition as it is a continuation of the sample-drunk playfulness of De La Soul’s 3 Feet High and Rising, Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique, or the Digital Underground’s Sex Packets. It borrows from the past, delights in the present, and anticipates the future.”

Creative Futures (Ford Foundation, October/November/December 2020): One reason I launched Dada Strain is to put down on “paper” some ideas of what “Next” can be like, and start making stuff for it. It’s my participation in making a world that I want to help build, that my colleagues and talented, ethical people across communities far and wide can do their best work in, a world that values work with some meaning and purpose (in all the different connotations of those words) beyond strictly commercial value. But before one can dream that shit up, there are questions that need asking about the future of creative endeavors, how we get there, and what to consider. This fall, Ford Foundation commissioned 40 essays from a bunch of smarties on a range of subjects that deal directly with the structural issues that affect creative futures: localization, co-operation, new models, funding, infrastructure, and of course the new ways of making stuff. I’m still making my way through them, but they’re useful, heady reads.