Chart Mining: Rise of the Jamaican Virtual Reality Artist

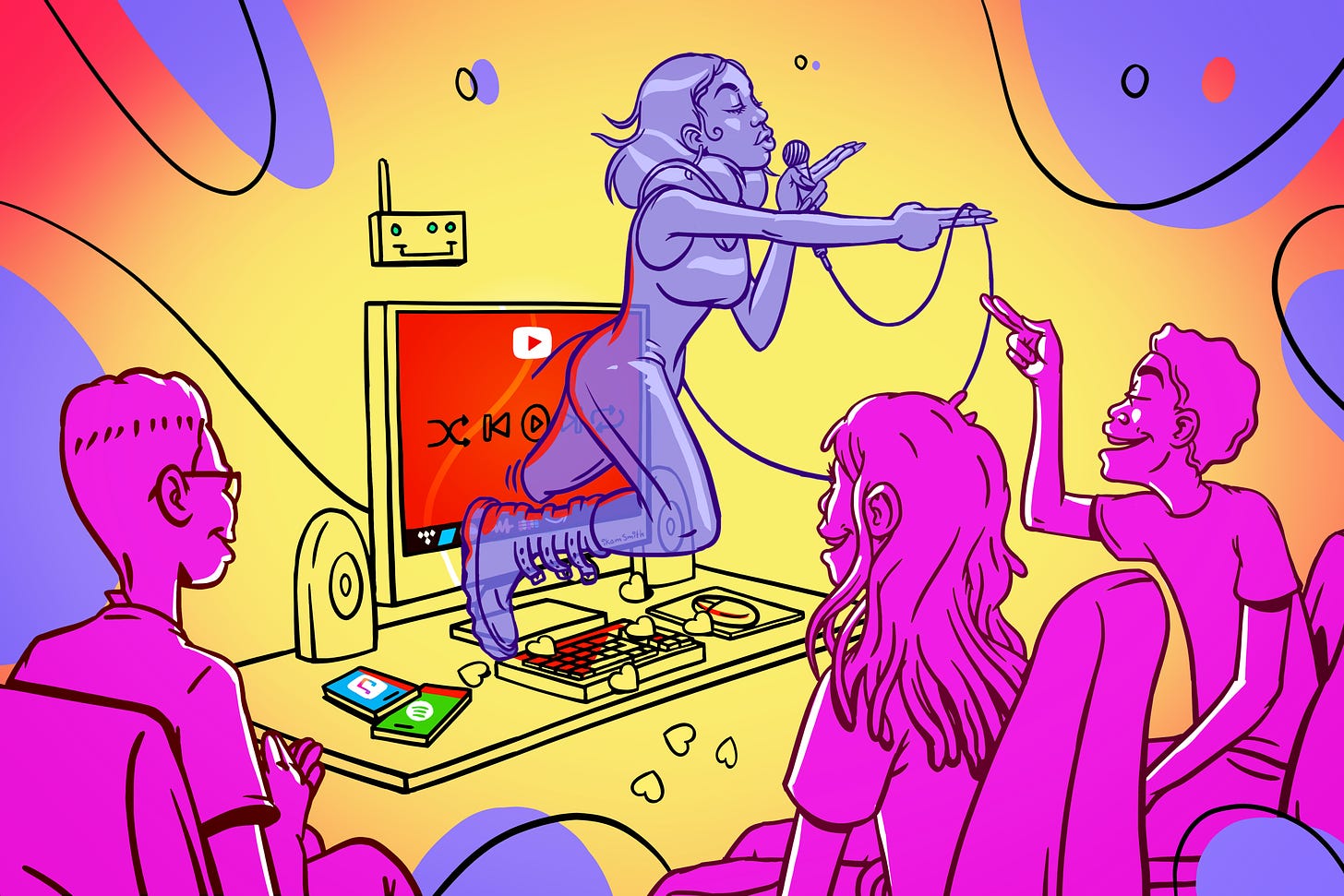

Essay by Jordan Chung: First World tech's push for a digital-music future is creating bizarre artist habits and territory-specific inequities in places traditionally rich in sound.

The first Dada Strain contribution from Jordan Chung (a.k.a. Time Cow) is an artist’s view of the “streaming industrial complex” from a country where the new rules are imposed from the outside, and the trickle-down flows extra dry. Even beyond our pandemic times, the disruption in how music is released and how audiences consume it, in one of the world’s most influential music cultures, is worth the questions.

It’s mid-afternoon, you start daydreaming about what to eat for dinner. You think about when and what you’ve eaten before, if you will need something light or something filling and lasting. Whatever your financial state, in the absence of outside support, neglecting these thoughts will have you cooking while hungry, or waiting for food service on an empty stomach.

Now consider the fate of the data-engrossed musical artist in 2021. The artist surveys the dreaded “content,” acknowledges their current statistics, anticipates trends, and then engages platforms in such ways as to fulfill immediate and forecasted content requirements. Hitherto, these were functions shared by the artist and their label, but the responsibility, analysis and action now rests with individual music makers. Faced with daily prodding from the streaming industrial complex and unpredictable social media trends, artists who know consumption of their work is now almost exclusively digital must produce music guided by these factors.

With the Jamaican music industry held in a chokehold by First World practices, statistics are employed to usurp minimal cultural impact and act as the sole benchmark for success. Ignore the sales reports. Spotify streams, YouTube views, AudioMack plays, and Instagram followers are the metrics of the day, with occasional Apple Music Reggae chart placements as a footnote, and the coveted Grammy a near-mythical crown. The first indicator of disastrous inequity in using such data to quantify success is that Spotify has only just become available on the island nation. Apple Music also opened its doors for streaming relatively recently (April 2020), with a debit/credit card requirement for sign up. While there are over four million debit and credit cards in circulation, limited online financial literacy, restrictive banking rules, and people’s habits ( where even radio stations are not willing to pay for music) means that Spotify will have an issue getting premium subscribers en mass. Add to that Spotify’s low royalty rates, as well as their restrictive free UX, and mass migration from established listening platforms may be slower than expected. What Jamaica has is unfettered access to inexpensive video production. So YouTube’s ‘Trending’ is an immediate and reliable metric—as is Audiomack, where songs can be streamed for free offline. Yet the ability to sustain a career by using YouTube and Instagram as mediums to distribute music—and, subsequently, proselytize and exaggerate statistics from multiple platforms—has given rise to a deceptive kind of star, what I call the Virtual Reality Artist.

In a recent UK Parliamentary inquiry on the economics of music streaming, executives from the majors (Warner, Sony and Universal Music) noted that this has been the most commercially competitive era of music over the last 30 years, an atmosphere that has liberated artists and labels from formerly commonplace industry practices. Gone are the days of artist development and the marketing of talent, replaced by virtual reality artists who are scouted via social media apps. Chairman and Chief Executive of Sony Music UK and Ireland, Jason Iley, pointed out that in the past year, of the top 20 American artists his labels signed, many had been discovered via TikTok. As of January 2021 at least two songs (one making it to #1) on the Billboard Hot 100 were TikTok-kickstarted. The digital world is being exploited faster than laws can keep up. Jamaican artists try to compete but are slow to react to trends, or get blocked from accessing mainstream structures, and thus end up propagating exploitative systems.

Jamaica has been a timeless influencer of Western pop music since at least “My Boy Lollipop,” a constant borrower and lender of styles, central to global pop music’s give and take, interlocking the fates of the small island and big industry. We also typically try to mimic business practices as far as we can observe. So today’s Jamaican artists who gfew up watching Vybz Kartel reach the top of our pops by releasing up to four songs a month follow his lead. Little or no access to statistics that quantify the financial viability of such an approach—ignoring economies of scale at play, and accepting the continued worldwide growth of popular artists—has meant this strategy became normalized in Jamaica. Where this would be cause for concern for career musicians with an understanding of the business of music, not even the Jamaican music business itself has 100% caught up to digital consumption trends. The young VR artist is at the centre of their own reality—and this new reality has created its own ecosystem. So now in addition to maintaining a high volume of releases, the artist has to create engaging content in the hopes of going viral on YouTube or Instagram. To keep releasing music at a high pace in an environment where no artist wants to share a riddim, artists and their trusted labels have often outsourced procurement of riddims to beat farms such as BeatStars. To mine the value of music videos and Instagram posts, other workers in the VR economy (YouTube vloggers and InstaGram comedians) rework the video/audio content to promote themselves and the music simultaneously.

Producers and labels get riddims from friends or download them from BeatStars producers. The work is done so quickly that sometimes the “Purchase your tracks today” tags are still embedded in the riddims that new vocals are recorded onto, and are released via YouTube or Audiomack. When you purchase the tracks from iTunes or other digital outlets, the tag is no longer there, and sometimes a more refined vocal mix appears. This indicates that at some point after the YouTube/Audiomack version, an agreement was reached with the composer of the riddim to remove the tag. Without the tag, the official digital distributor can now upload the music to more discerning commercial platforms without copyright violation claims. (While not completely dissimilar to the American situation where makers of TikTok hits have found themselves at the mercy of third-party copyright owners, in Jamaica the beats are pursued before they go viral, and the buy-out terms favor producers.)

Artists declare commitment to this system by seeking to create their own Vevo channel. Because that video streaming service is a recognized part of the music business (Vevo is owned by a consortium that includes the majors) serviced by digital distributors and labels, consumers are assured that the music they find there is made up of official releases. The Vevo channel becoming the de facto source for the latest songs from an artist means an end to hearing “Yow Krish Genius!” or “Akam Entertainment!” or “Yuh know a Warstar” or other promotional call-outs. It also cuts down on career-minded Youtuber influencers playing Christoper Columbus with music releases. The other meaningful change is that by placing a song on Vevo, its view-counts will no longer be spread out across multiple unofficial channels by multiple uploaders—or syphoned off by fake videos—becoming a more reliable metric for accruing the critical views which are VR artists’ lifeblood. But if you meet the view-count Buddha on the road to statistical quantification, kill him; these numbers are nothing but ghosts, since they’ve long been for sale or gamed.

Still, for VR artists, YouTube/Vevo views are the hot commodity. In a virtual market, it's not one million dollars that’s the quintessential prize, but one million views. YouTube is the KFC of music in Jamaica: you go there to get fast music fast, and it's always jam-packed! Any Jamaican can log onto the platform to see which song is popping. If a song was popular locally and it’s not available on YouTube’s Trending, a screenshot of the evidence will certainly be made into an Instagram post by an artist, popping up on their multiple fan/updates pages (which may be secretly run by the artist themselves). The same is done when an artist hits one million followers/subscribers on any platform. Trending songs and controversial Instagram posts are boosted by YouTube vloggers, who then act as tabloid podcasters, speculating about the song/post. If the song is popular enough, Instagram comedians do voiceovers driving their own viewers to the song(s) on YouTube. To convince the Internet-connected Jamaican that your song is a hit without millions of YouTube views, or with less than 10,000 Instagram followers, is like selling them a tin of corned beef without the key. Wah dem ago do wid dat? So the VR artist consumes the content across platforms made about them, checks the relevant follower/viewer stats and decides their future direction based on the most views/likes.

Artists who embrace this ideology can end up stuck like Dale Cooper in the Black Lodge. They’ll emerge sometime later, trying to catch up to themselves in reality, back to dealing with the same issues the average artist has faced all along. Statistics such as view-counts and trending rankings can quickly indicate what fans like, but using this information to simply one-up the last song/video with more vapid content leaves the artist trapped on the Internet. These thoughts surfaced in casual conversation with my colleague Gavsborg regarding the controversy surrounding Christopher Tufton, Jamaica’s Minister of Health and Wellness. To wit: In 2020, dancehall artist Govana made a series of songs centred around the love lives of himself and a protagonist, Chris, who is constantly being cheated on by women. The health minister’s scandal was also of a romantic nature; yet Govana’s failure to tie these songs to a major gossip event so fresh in the Jamaican consciousness, means that while the videos were cool and the songs hot for a few weeks, they were replaced by next week’s trending songs. In an age where politicians purchase custom dubplates—and a Jamaican political environment not as “shooty” as that of the 1980’s—Govana blew a chance to create a track that would be remembered for as long as the minister is alive. This is not to say Govana is a VR artist, but there are monumental opportunities being missed by those not interacting with real-world events/culture.

You can forecast the inevitable crash of a VR artist by using confirmed audience math and financial metrics: Jamaica has a population of roughly 2.8 million people where only ~53% (or ~1.5 million) are connected to the Internet. This figure is further reduced to people who have do not access restrictions by virtue of territorial availability, language, content and context of the music. If you’re popular enough to have one million of those people play your song—or multiple views adding up the coveted one million—you could gross $100 to $1700USD. (If you’re a musician, please ask your digital distributor how this calculation works.) For the unfamiliar, money made from YouTube views depends on what region your video is being viewed in (Jamaica/America/Canada/etc), on the amount spent on ads in the viewers’ region, on the run-time viewed, and on the type of device used to view the video (no banner ads on mobile). If your viewership is mostly Jamaican via mobile phones, with no ads on your page, income looks grim. Add the 1.6 million people of the Jamaican diaspora and you still end up with maybe an audience of around 2 million who can access the music, so it is possible to generate marginal income based on the viewer’s region. An artist popular enough to be averaging one million views a month will have management taking sometimes 10-20% of income and a distributor taking another 15%. That’s up to 35% now gone, while the artist has to pay for the video that was done at $250USD minimum, the talent(s)/props in the video, and online promotion.

Some artists throw minimal income to the wind to live vicariously through their single location music videos, but others master the Virtual Reality. Embodying the ‘Chop Life’, an artist like Gold Gad continuously validates his career entirely via the Internet. If things were governed solely by statistics, Gold Gad would be one of the biggest artists in Jamaica—so according to Schrödinger’s Stat, he is. But if the songs are not selling, it’s both one million views and one view. Chronixx, Koffee and other popular Jamaican acts have done live performances via Instagram, sometimes aided by major sponsors, with viewer counts in the thousands. Gold Gad goes live at set hours of the weeknight with upwards of 30k viewers, and accumulated viewership counts of up to 200k. His live streams are X-rated, but he may be creating a new local paradigm where artists use their platform for live video interaction, to advertise or sell merch.

For now artists make money from their virtual popularity for a limited time through adverts, jingles, dubplates for sound systems, requests to voice on riddims and live shows. But coronavirus has drastically reduced dubplate and live show income which are the main earners. With minimal financial returns online, what is going to happen with increased Internet connectivity worldwide and more artists eventually sharing the same virtual space? With a large pool of VR artists, touting the same impact statistics, the value of all artist works drops significantly. Every artist will have a million views, dissolving the stat’s potency. If everybody is rich, nobody is rich. What happens when an artist is the first to reach a million views on a new, locally accessible, popular platform? Without a catalogue outside the Internet, an artist living this current YouTube reality would cease to exist. Currently, any popular-enough dancehall artist or song can gain a million views in two to three weeks. Creating a hubbub about such an achievement already makes artists seem desperate.

Artists looking to prove their worth outside of the Internet will have to go back to placing emphasis on who sells the most, where views are simply counts of fans being transported to a purchasing point and not the point itself. Can your music sell? Can your music push the consumer to purchase products associated with your likeness or your music? If that’s not the case, the other option is to do away with selling music completely — and I don’t think I’m ready for that conversation. A world where praises were heaped upon Vybz Kartel and Buju Banton’s recent albums whose combined first-week sales were not even 5000 copies, is a mirage. Virtual Reality artists are the frogs in the boiling pot of water. It’s gonna be too late by the time they realize the end is near. Until then I’ll be using tried-and-true standards of the Jamaican listening experience. Gavsborg uses the metric of walking through downtown Kingston and hearing what’s playing to know if there’s a buzz about a song or artist—and it’s 100% reliable. My metric is to listen to the latest mixes by the DJs in the arcade in Half Way Tree, or in the taxis and buses.

So while we’re here focused on how to eat a substantial dinner today, the rest of the world has come up with a completely new diet, having smaller meals more frequently, pushing the old money at every new urge for something sweet. We can try to follow but considering our size and habit of punching above our weight class we may land in a very unhealthy situation.

Jordan Chung is a writer, photographer and musician from Kingston, Jamaica. He is best-known as one of the producers of the great Equiknoxx Music. Follow him on IG and Twitter.

Ikem Smith is an illustrator, animator and writer who lives and works in Kingston, Jamaica. He has ideas and tells stories:, check out his work on IG and Twitter, and hire him at IkemSmith.com

This is a fascinating insight into how the new world of music making functions. From making riddims at Channel One on Maxfield Avenue to ‘buying beats’ on line ! Rahtid (‘;’)As the old Buggles song goes “video killed the radio star” but that’s no longer the case.

very much still digesting this, but wow, really interesting / thought provoking. Thanks guys.