Amirtha Kidambi’s Liberation Sounds | Bklyn Sounds 6/5/2024—6/11/2024

A Q&A with the vocalist of the "spiritual punk" quintet, Elder Ones + Shows: 'Public Service' / Rebekah Heller Bassoon Ensemble / DJ Spinna's 'Soul Slam: Prince' / Steam Down + Lovie / more

As is the case with many folks in Bklyn’s improvised music community, I first met Amirtha Kidambi through the late jaimie branch, and aspects of their kinship seemed instantly obvious. The high-level of musicianship and improvising acumen was expected. But they also shared an unrestrained passion for the power of music, visible every time either of them took the stage, in endless combinations with an increasing coterie of community co-conspirators. And then there was their mutual righteous rage at a world gone wrong, the overwhelming desire to have music be a marker of a social change that both demanded of the world. They called each other “comrade” — Amirtha still does.

I have never ever seen or heard Kidambi, a vocalist and multi-instrumentalist, first-generation Indian-American woman, and whip-smart and funny-as-hell educator, take the stage without expressing her feelings about capitalism, racism, patriarchy, and our collective need throw off the colonial chains that bind us. Beyond general agreement, my respect for her never-quit-ness in any context, is absolute. And in the shadow of the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza, Kidambi, a longtime advocate for free Palestine, has brought her activist activities even further to the fore. As if that was possible.

Though the music on New Monuments, the third album by Kidambi’s long-running and oft-mutating band Elder Ones, was created long before last October 7th, when the world once again lurched towards unspeakable horror, it is a weighty soundtrack for our times. The album consists of four long pieces. Loud, boisterous fusioneer-ing music that Kidambi calls “spiritual punk,” it is a part of a conversation that Kidambi constantly raises: how everything really is connected, the atrocities and the liberation potentials, how history requires a deeper understanding and a reset. In this, New Monuments takes a rightful place next to recent work by branch’s Fly Or Die, and Irreversible Entanglements as political statements from the so-called “free jazz” world, not simply angry roars, but works of immediate intention and long-term forecasting.

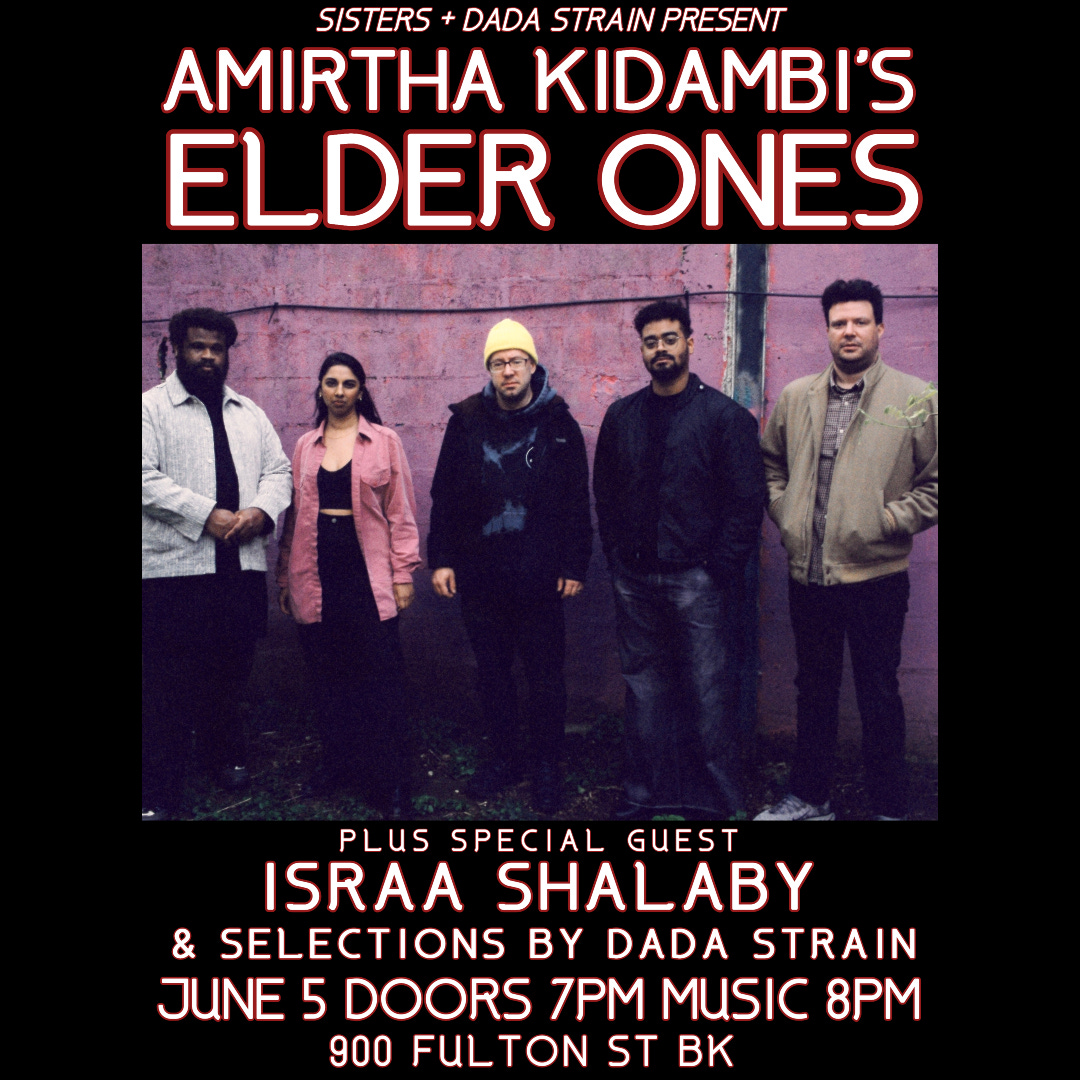

On the occasion of presenting Kidambi’s great current version of Elder Ones at Sisters on Wednesday, June 5th — a band that now features Kidambi on harmonium and vocals, her long-time Elder Ones partner Matt Nelson on horns, Lester St. Louis on bass, Jason Nazary on drums and Alfredo Colon on soprano saxophone, and all of them on electronics — I took the opportunity to talk to Amirtha. The conversation touched upon how she came to improvisation, about the political and social aspects of improvised music, and about what it can say and do for the world at large, at a time like this. We closed with a list of organizations and initiatives that Kidambi and other members of Bklyn’s DIY community are working on to help the Palestinian cause. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

I describe you as a vocalist, composer and improviser. Tell me a little bit about how you classify the kind of work that you make, and how you started that work.

I've moved away from even this term composer because it has a particular kind of hierarchical connotation. I usually say these days that I “create music” rather than “compose music.” I feel very in-line with the lineage of creative music, and I also enjoy that formation because it asks more questions than it answers <laughs>. It's an interrogative practice, like the AACM and the Art Ensemble [of Chicago], a formulation of a composer who performs, who improvises, who's co-creative with the people they play with. This feels good to me. It also doesn't feel tied to one genre or way of making music.

My trajectory was as a performer, from Hindu devotional music when I was a kid, and as a Bharatanatyam dancer, dancing to Carnatic music, and really embodying that in my feet and in the rhythm. And then studying Western classical music in school as the default, and being a performer in that sphere, then with new music kind of rediscovering improvisation. Improvisation is such a part of my home [South Asian] culture, but it was sort of beaten out of me in my [formal classical] training. I rediscovered it in New York, partly because I was doing so much musicology research on the AACM and Cecil Taylor and a lot of improvising musicians.

I found myself seeing them as critical interventions and realizing that there was a lot wrong with my music-making practice for myself: that it was Eurocentric, that it was hierarchical, that it was elitist. So I just started improvising with a lot of musicians in Brooklyn, one of whom was drummer Max Jaffe, who was in the original iteration of Elder Ones. Elder Ones formed more officially in 2015, when I had the Roulette commission. It was soon after Eric Garner and Mike Brown were killed. I think the first Elder Ones performance was at a Matana Roberts fundraiser for Mike Brown — or it was a trio version, not called Elder Ones yet — our first piece was for Eric Garner.

That's really where this band is coming from. The first official Elder Ones quartet show — me, Max, Matt on reeds and Brandon Lopez on bass — jaimie branch invited us to play at Manhattan Inn, also before the band even had a name. (jaimie's definitely part of that early history, a comrade that I felt very aligned with.) It has always just been explicitly political. Everything I do has that kind of critical lens to it, but Elder Ones is the most explicit, it is the vehicle for my musical activism. I do a lot of contextualizing on stage. I talk about what each piece is about, and what we're trying to do, and what the music is for. Elder Ones is a project that is explicitly about collective liberation, about connecting to that history of Black music, carrying the tradition forward of being liberation music.

Can you talk a little bit about that? About how, in your experience, improvised music — whether that’s free jazz, or other improvised traditions — speaks to liberation?

For me, it became this really critical intervention in my own life. I've looked at this as a liberation music in line with the idea of decolonization. If we're talking about Indian music or African diasporic music, these are social formations, right? Community music, as you say. For example, I grew up practicing this song-form called Bhajan, which is call-and-response music, in a way that is very similar to spirituals and gospel. Full of hand-clapping and hand-percussion and harmonium and call and response and everybody has to sing, everybody has to play, everybody has to do everything. It's not performance, it's an ecstatic spiritual devotional practice.

I think what got beaten out of me when studying this Western point of view, was that [music] became less embodied. It became more intellectualized, more codified and theorized through this kind of fake system of theory and harmony, all these things that were taking my body out of the music. Whereas improvisation is just inherently an embodied practice. This is one of the things that colonization was good at, saying that anything of the body is base, anything of the body is bad, anything of the body is low.

And I feel like jazz and improvised music — it's dance music, it is of the body. This obviously doesn't make it less complex or less intellectual. I needed to go to the body. As a vocalist, it was really crucial because I was trying to find my voice again, that voice that I had before I went through training that sort of ironed out my individuality, my history and the origin of my culture. Improvising was a way to go back and find my voice, connect the traditions of my own community through Black music, which is American music. And the embodiment is a part of it.

There was a communal aspect as well. I put so much pressure on myself of what a composer was supposed to be, and improvisation allowed me to create without having to worry about that. You know, “Just play!” I started to realize that I had a creative voice by improvising. I’d played in rock bands when I was younger and I’d made music, but I was always tying myself in knots about songwriting and saying, “I don't really know how to write a song.” They would all come out 20 minutes long <laughs>. So now I found my format, 'cause for improvisation that's totally fine.

Also I wanted to play with more people of color, play with more people of different gender identities, different types of people, especially coming out of classical music where I was around a very homogenous group of people. I will say this is more in the creative music and improvised music community, and distinct from the jazz community per se. Here I was seeing a lot more different people, and I could seek people out too.“Who's that person? They're so cool. I love their music. Let me go play with them.” Sometimes we would only talk after we first played. It's such a great way to build a community.

So, improvisation is a social practice. It's a critical practice. It's a decolonizing practice. And a political one inherently. George Lewis's book was a big mind-blower for me in grad school. The explicit connection of the AACM being modeled after the Black Panther organization: their infrastructure, their charter, their organization, their community involvement, community music, school, food programs, all this kind of stuff. It's collective, all of that. It was like, that's how I wanna do things.

I'm even uncomfortable that I'm a band leader. It's not my ideal. I try to be, especially in the music, as collective as humanly possible, even if I'm the one sending all the emails, <laughs>, you know? [In Elder Ones,] they are my conceptions musically. They are aesthetically the things that I gravitate towards. Like, I'm really into punk. I'm into noise. I'm into rhythmic grooving music. And it's informed by a lot of Indian music and late-’60s/early-‘70s spiritual and fusion music. I love that stuff. So it has my aesthetics, but I could never fathom telling anyone in the band how to approach the music. That's really co-creative and everybody brings their own way of doing it.

I read this great article by Matt Robidoux. I did a unit in my class on disability and improvisation, and how that's another area in which when you don't prescribe the way something has to be played, how much more accessible music-making becomes. The article was about Pauline Oliveros AUMI system, which is a musical interface that allows people of various abilities to use micro movements to play. And it was through improvisation. Or my students who don't read music: we can immediately make music together. Improvisation just levels things in a way that is so crucial. And it is ephemeral, it's so much harder to turn into capital, it makes you have this communal experience, not being able to grab it, not being able to codify it, and turn it into a product as easily. We try, we make records. (To me, it's a hilarious endeavor that we do.) But the record is a document to me. And the real thing we're doing is the performance and the audience is part of that. It's about being present and together.

We live in such a corporate, platform- and institution-driven world around culture nowadays, that folks increasingly dismiss music’s ability to affect political or social change. Can you talk a little bit about the nature of trying to make political statements with music, particularly now? Maybe speak a little bit to what you think music — as opposed to the product of music — can actually do for people? What do you feel that you, as a musician, can do when you perform?

Music has always been part of social movements. It's always bolstered social movements, always given energy and inspiration to social movements. So I don't see how anyone could make the argument that it doesn't matter. For me, Nina Simone is the ultimate figure of that. I’ve been thinking a lot about Miriam Makeba having to leave South Africa during apartheid and work in the United States. And Mingus, Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln. There's so many examples in this music and this lineage. I've done a lot of research on Bernice Johnson Reagon and Sweet Honey of The Rock. I've participated a lot in protests as a musician and see what it does for people to be marching to rhythms, to have people singing and playing, instead of just chanting all day. It does so much for the spirit.

I'm a teacher, so for me, context is everything. Sometimes I think I talk too much on stage. But actually, the thing that gets reinforced every time people come up to me [after a show], they're like, “Thank you so much for talking specifically about what the music is about.” You know, I'm talking about Edward Said and Orientalism and Imperialism and trying to make connections between the farmers protests in India, and Islamophobia and fascism in India, and the quiet Muslim genocide, to what is happening in Palestine, what's happening in in Haiti, Congo, and Sudan. There's been so many of these big popular uprisings, especially in the last handful of years, obviously after George Floyd.

And that's where a lot of [Elder Ones’ New Monuments] really starts, in 2020. Before we were playing together, I was writing this music. In 2021, there were huge protests around what was happening in Sheikh Jarrah in the West Bank. There were women's protests in Iran. These huge, major collective movements. And there's a reason why art and music gets censored by the powers that be. I’m moving away from even saying “political music” and more towards “liberation music” because politics makes it sound like the politicians or the parties have something to do with it. It's really about liberation from systems of oppression, which are so intertwined. And what I'm trying to do is contextualize it and ground it, connect all these different things together so that no matter where we're playing, it makes sense.

It's all connected. So for me, it is providing the energy, reminding people not to compartmentalize. It can be this collective thing that we're doing together. We can be in our bodies for this hour and a half [of performance]. It doesn’t have to be a depressive thing that you do alone with your phone. And it does matter. Because right now, [what’s happening in Gaza] is not being perceived the same by every person, everywhere we go. It's not preaching to the choir.

In Germany, I've been very explicit and it's been pretty intense. There's been a lot of backlash. But I'm trying to contextualize as much as possible: “Look, [Free Palestine] is a movement led, first of all by many Jewish people who are saying, ‘not in our name.’” They don't see that in Germany. They don't know that because there's not many Jews left there. [And I say], “Well, I'm coming to you from New York City where we are side by side, Jewish and Palestinian folks and everybody else marching.” And it sparks these conversations. After one show, we met these artists from Namibia and Liberia — and, of course, there was a Namibian Genocide in the early 20th century by Germany.

It becomes a way to talk and connect with people from all over the world — to hear, for example, about what's going on with the far-right movement and the AfD (Alternative for German) and what does that have to do with antisemitism? It's not easy. I can't tell you the number of emails that I've been writing after this last tour. And for me, we can normalize Palestinian solidarity, especially right now. We have to be able to call it what it is. It's also a responsibility to fight the counter narratives and the insane misinformation, away from screens, away from the algorithm, just in front of people. This is crucial.

Talk a little bit about the organizations that you’re involved with, so I can add the links, and people can get involved — both locally in Bklyn, and more broadly, around the music and cultural communities.

The main thing I'm involved with is called Amplify Palestine, which was the organization that put together the BDS mixtape that jaimie branch and I were on. The BDS mixtapes are a benefit to send funds, and set up partnerships with things like the Freedom Theater in Jenin in the West Bank. And through that, we formed a music-specific subgroup called Musicians Amplifying Palestine, where we work on direct actions like sending musicians to specific demonstrations or performing. There are more volumes of the BDS mixtape. One of the arms is organizing live event benefits and fundraisers. The subgroup I'm really working with is the Institutional Group, which is trying to get organizations in New York to endorse BDS and sign on to PACBI, the Palestinian Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel. Poetry Project is one of the organizations at the forefront of this. We are trying to sort of agitate around it in the music sphere. And we've gotten a lot of the smaller DIY spaces to commit. It's a slower process, but we're working on some of the bigger institutions to make divestment happen across the board. Even if music venues don't work with the state of Israel and don't get funding from the state of Israel, just make it explicit. It's like the anti-normalization of South Africa, it's the same tactic, it comes from the same history.

[For the benefit aspects of the Elder Ones’ Sisters show], I picked a family from Operation Olive Branch, which has this insane database of people who need direct mutual-aid fundraisers. The family is a small family — Mahar was an emergency room nurse, who has been displaced multiple times, and she, her son and husband are in the southern part of Gaza now, near Rafah and trying to evacuate. We're gonna have links and try to get as many donations as we can at the show. There's an endless number of things to be giving to right now, but those direct fundraisers are going straight to a single family, and that is really important. It's manageable. We can actually kind of see tangible results.

Also this Saturday, on June 8th, there will be big demonstrations happening all over the country. There will be stuff in Brooklyn for sure.

Amirtha Kidambi’s Elder Ones + Israa Shalaby + Dada Strain (DJ) (Wed 6/5, 8p @ Sisters, Fulton Street - $25)

This Week’s Shows:

This is a record release party for an exceptional about-to-drop compilation, IYKYK, a project curated by the DJs 4AMNYC and Varsha, that champions femme and nonbinary talent from underground dance music communities worldwide. The track-list features a quietly star-studded line-up, a few of whom are on-hand at Gabriela, including Haruka, JiaLing, Russell E.L. Butler, and Tammy Lakkis. (Wed 6/5, 9p @ Gabriela, Williamsburg - FREE w/RSVP)

FILM: Straight out of history’s central casting, National Wake was a multi-racial punk band in Johannesburg, South Africa, who existed for a few years in the late-’70s/early-’80s. Yes, they had some great tunes (check out “International News”), but from this vantage point, the music pales next to the story of a group whose very existence was illegal during Apartheid. Directed by Mirissa Neff, This is National Wake is a 2022 doc that tells this story with context and power. Followed by a Q&A between Neff and the mighty punk professor, Vivien Goldman. (Thurs 6/6, 7p @ Roxy Cinema, Manhattan - $17)

New Weekly Event Alert! All summer long, Industry City in Sunset Park will be hosting a great free-music series in one of its outdoor spaces — and the line-ups are kinda crackling. Maybe few as great as this opening night, on which Chicago’s mighty fire-breathing saxophone spiritualist, Isaiah Collier, will team up with Bklyn’s record-selecting maestro of community events, DJ Spinna. But as with many such location-sponsored events, it will only be as good as the crowd, so consider telling a friend and making a summer evening of it, if you’re in the neighborhood. (Full disclosure: Dada Strain will be presenting there in August.) (Thurs 6/6, 7p @ Industry City, Sunset Park - FREE)

Lebanese-American DJ/producer Tammy Lakkis is one of Detroit’s great young talents, who’s been playing more and more in Bklyn post-lockdown. Her sets are informed by the D’s foundational techno/house history, but also not fully beholden to that sound, comfortable in a global setting. Tammy is great at selecting for the context. So Mood Ring may get the best, most-surprising Happy Hour DJ set of the summer. (Thurs 6/6, 7p @ Mood Ring, Bushwick - FREE)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dada Strain to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.