On Phil Lesh and the Long Now | Bklyn Sounds 10/30/2024—11/5/2024

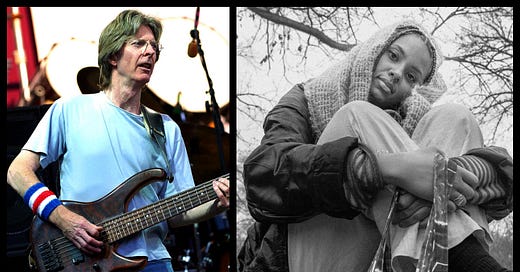

The Grateful Dead's bassist, the value of aging, the question of time + This Week's Shows Include: Ursula Rucker, Tim Motzer & Gintas Janusonis / The Cure album release party / livwutang / more

No, I did not expect to write about the Grateful Dead twice in four weeks, but sometimes circumstances are what they are. Yet once Phil Lesh passed away, on Friday, October 25th at the age of 84, there wasn’t really a question. So, “Thank you Phil!”

On March 15th 1990, the night of bassist Phil Lesh’s 50th birthday, I went to see the Grateful Dead played the Capital Centre in Landover, Maryland. Not yet of drinking age and still filled with the foolhardiness of youth, I was a subscriber to a certain kind of ageism at the cost of valuing experience, even if I’d already begun reconsidering my position. Listening to the Dead played no small part in that reappraisal, as did watching jazz musicians like Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman and Sun Ra (all of whose work I’d started delving into more deeply at the time) approach their twilights with creative vitality fully intact.

Phil was the first member of the band to reach his fifth decadental milestone; he was in fact, the first member of any classic rock group then still-touring non-nostalgically to move past middle-age. The whole “hope I die before I get old” stereotype was beginning to get exposed by circumstances. But in the chatty, catty Dead parking lot, Phil’s age gave rise to gossip that Lesh was soon going to quit the band, a rumor that got so hot by June, he had to address it from the stage, which he did with gusto, calling it a “bullshit lie.”

It was perfectly in character for Lesh to play the part of the community’s wiser, weirder, older uncle, as it seemed his role in the band. He’d always been the one with skewed perspective, who brought the atonality and broadened the Dead’s musical aspirations in a way that transcended its rock, jugband and R&B roots goofing. Lesh is the one who went to Mills College with Steve Reich, who introduced Coltrane to the Dead’s listening diet (though drummer Bill Kreutzmann arrived as an Elvin Jones freak too), who brought in a friend that played prepared piano (Tom Constanten) and initiated Anthem of the Sun’s tape-layering fantasia. He was also a thoroughly unique bass player (shout-out to Jon Pareles for the great descriptions), a psychedelic loon, and a foil for Owsley Stanley’s gearhead-mania. Yes to all that—though it’s also important to note that at the band’s 1972-74 height, he could, alongside Kreutzmann, swing like a m*therf*cker in almost any context.

Yet Lesh’s avant-garde rigor came equipped with a history-minded conscience. His understanding of musical lineage and evolution differed from his bandmates’. Phil’s combination of vision, pedigree and assertion allowed the Dead to present music that lead guitarist and ship captain Jerry Garcia could jump on naturally, but often did not himself initiate. Lesh bulldozed into these directions, and did so in numerous ways. He could access the emotional poetry of universal thinking (think “Box of Rain,” one of his few band compositions, co-written with Robert Hunter as an elegy for his father); but he also regularly launched new-music excursions by sonically stretching time (think the Seastones “jams” with Ned Lagin, or any number of “Dark Star”s or “Other One”s ) to bask in absolute sound freedom.

From their 1964-65 get-go, until the Dead’s 1995 conclusion (even beyond it), Lesh’s comfort with personalizing the breadth of music’s possibilities was unparalleled in a band where, at any given moment, many strong points of view fed the scenario. When in 1985 a graying Deadhead told a young me outside Nassau Coliseum to “Listen to Phil! When he’s on, the band is on,” I heard it in “Dead show” terms. Yet continuing to listen to Phil play his six-string bass—and, later on, reading his occasional interviews, or his memoir, Searching For Sound—meant understanding how his approach also informed a deeper consideration of time, and time-keeping. In his mind, these measures were not small pools of unique experiences we jump in and out of, but a river we’re constantly bathed in. Momentary circumstances dictate only so much, while developing—and even trusting— your own long game, is crucial to living a true life.

Which is maybe why, when Phil’s 50th birthday rolled up around the milestone of my 50th Dead show, Lesh seemed like a good model to a 20 year-old reassessing how embracing age and experience could inform one’s own path. And also for how living in the moment was related to abiding another definition of Now. In fact, the longer I watched and listened to Phil—which I did more than any surviving member of the Dead, from my first show in October 1984, to the great roundtable on the American composer Charles Ives from earlier this year, that Ethan Iverson posted last week—the more I identified with the notion that what we do with our time is much richer than how we manage our individual day-to-day. How we use our living moment should inform—or reform—what came before, while also leaving legacy for what comes after.

Phil Lesh did this in a variety of ways. The music education aspect kind of spoke for itself. Though Lesh did join major Dead reunions of the past 29 years—and notably, sat out the current Mayer & Co. fiasco—his main musical outlet was Phil & Friends, a constantly rotating cast of live collaborators that spanned generations and worlds. Since its 1998 debut, Phil & Friends had included all living members of the Grateful Dead, jammy rock stars, jam-band superstars and kids on the come-up (who now command major stages), contemporary jazz greats and improvising also-rans, Bay Area folks Lesh respected, random experimentalists and singer-songwriters, and by the end, even his own son. Some would stay a weekend, others for a few years. And the repertoire regularly dipped into Miles and Coltrane tunes, amidst the classic-rock and Dead nostalgia you’d expect. The pay-it-forward see-what-happens ideal was amazing to witness. (Even if I went too rarely.)

But it was Phil’s constant returns to the Dead as cultural infrastructure—or as contributors to that infrastructure—that continued to keep Lesh current to me. In 1997, the 50th birthday show I attended, was released on CD under the name Terrapin Station (different from the ‘77 studio album) to raise money for one Lesh idea: building a musical venue/Dead museum. The thought was that a local Bay Area space could be a clubhouse where the band’s members played whenever, their own permanent residency hall. (It was, I think, at least partially inspired by Garcia’s 1995 death, and the ensuing talk of how the road contributed to the Captain’s substance abuse and demise.) The initial plan fell through, but in 2012 Lesh built that venue, Terrapin Crossroads, in San Rafael. It hosted Phil and other Dead members, while booking both local and international acts, and was only shuttered by the pandemic. The Crossroads idea, and the need to minimize a 70+ year-old liver-transplant-recipient’s touring (but not playing), also contributed to Lesh’s years-long residency at Westchester’s Capitol Theatre.

It wasn’t just the club though. Lesh’s commitment to building things that withstand time’s scrutiny extended into other projects with a long-range perspectives—some via actual funding provided by the Rex Foundation, Grateful Dead Inc.’s long-running charitable foundation, and some by speaking about them to the press. There was his championing, alongside (but independently from) Brian Eno, of the ten-millenia clock which the goofy California utopians (inevitably including some of Silicon Valley’s most pernicious “thought-leaders”) at the Long Now Foundation are currently constructing. Lesh also spoke of creating the world’s biggest church organ, whose chords could last days, and on which you could theoretically play a piece that can be heard in the future. [ed. Admittedly, I am having trouble finding evidence of either comments…reader help?] The older I got, the more Lesh’s ideas began to intertwine with the way I understood Sun Ra evaluate sound, time and universal energy.

Which leads to the liver transplant that Lesh received at age 58. In his own life, it was likely the most important experience that addressed his own role as a nexus of the before and after of others. The Times’ piece on it is nice. Though it’s worth noting that Phil’s nightly donor raps—post-transplant, he opened each evening’s encore by telling his story as a survivor, and beckoning audience-members to register as organ donors—included more than a little bit of the metaphysical. He would invoke the relationship he now had with Cody, the name of Lesh’s liver donor (emblazoned on the bassist’s signature sweatbands), a no-longer-living person now responsible for Phil still being here. Any of us can, Lesh was saying clearly, leave behind something that allows others to live, so please take extra responsibility if you are able.

When Phish bassist Mike Gordon, a semi-regular Phil Friend in the late-’90s/early-’00s, saluted Lesh on IG last week, he wrote about one of their last conversations, “earlier this year.” In it, Lesh “mentioned that he sees the Grateful Dead’s music lasting for centuries.” You could read that as rock-star self-aggrandizement, which of course wouldn’t be wrong—boomer rock-bands are always in the right era for immortality. But there was something else to it, the notion of timeless truths that the Dead and Lesh recognized, tapped into, broadcast into the world, and saw quite a few people pick up on. The recognition that, if the broadcasts continue (and with the Dead’s archive, that’s not unlikely) there will always be fresh antennas for the signal, no matter their age — or The Age.

NOTE: I had by 1990 also begun writing about music for the American University student newspaper, which in turn led to an understanding of journalistic privileges I could use to get closer to my subjects. I used the opportunity of Phil’s birthday to apply for and get photo passes to shoot a portion of the show. No, I am not a good photographer (hence I married a great one - LOL), but they’re in focus and I figure worth adding to the canon here. Thank you for giving me those passes 34 years ago Dennis McNally. And, forever, thank you Phil. (More photos from the show on Dada Strain’s InstaGram.)

This Week’s Shows:

The great New York-born and -raised musicking multi-instrumentalist Casey Benjamin passed away unexpectedly in March, and has been eulogized and remembered a few times by many of the musicians he played with. Now, at the end of Robert Glasper’s annual Robtober stand at the Blue Note, comes an all-star concert to benefit the Casey Benjamin Memorial Fund. Some of the incredible folks appearing will be Glasper, Chris Dave, Derrick Hodge, Stefon Harris, Justin Tyson, Jahi Sundance, Lalah Hathaway, Bilal, DJ Logic, DJ Spinna, and Sekou Andrews. (Wed 10/30, 8p @ Sony Hall, Midtown - $$$)

Violinist Kaethe Hostetter has been deeply invested in the music of Ethiopia for a decade and a half. Before moving to Addis Ababa, she helped found Boston’s Debo Band, and in Addis, started playing in Qwanqwa, which she helped bring to Roulette for an incredible collaboration earlier this year. Hostetter’s solo sets are about loops and layers, and amazing melodies. (Wed 10/30, 8p @ Barbes, Park Slope - $15suggested)

Vocalist and improviser Fay Victor’s Herbie Nichols SUNG is a project based on the repertoire of peerless Manhattan pianist and composer Nichols, best-known for writing one of Billie Holiday’s signature songs, “Lady Sings the Blues.” Fronting a magnificent blues-jazz quartet, Victor adds her own lyrics and improvised inflections to what is essentially a cabaret vibe. But, oh what a vibe! In a world that occasionally needs reminding of the power of standards, without being crushed by outdated traditionalism, Fay and company’s imagining of things passed that are present, is a joy. Not sure how much of a one-off this project is, but it’s well worth catching up with. (Wed 10/30, 7:30 & 9:30p @ Jazz Gallery, Midtown - $25-$35)

Chicago vibraphonist Joel Ross has been one of the young it-guys in traditional jazz circles for a few years now—Julliard pedigree, Blue Note Records contract, playing with other it-folks—an estimation which often brings some creative negotiation. Whereas Ross hasn’t settled. There are swells all over his pieces, and a blues constitution, out of step with anything resembling current straight-ahead ideas. The folks he tends to play with—for this stand, one old friend alto saxophonist (Immanuel Wilkins) is replaced by another (Josh Johnson)—are equally unsettled. In a good way. The Vanguard is one of the last remaining cathedrals of New York jazz. Highest Recommendation! (Wed 10/30 - Sun 11/3 @ Village Vanguard, Greenwich Village - $40)

Let’s hear it for the tireless culture-making work ethic of garage-soul 45s DJ and relentless party-starter, Jonathan Toubin. F*ck, his 19th Annual HAUNTED HOP Halloween Spooktacular! looks absolutely great! The Mummies and The Gories for the heads, Kool Keith for the freaks, the yearly parade of great local bands playing as famous classic artists (The Thing as The Who, Shipla Ray as Depeche Mode, Gnarcissists as Butthole Surfers, and on and on). There’s also a garage-soul discotheque, installations, etc. all going til 4a. If you got the Halloween stamina… (Thurs 10/31, 6p @ Knockdown Center, Maspeth - $25)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dada Strain to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.